“Safe passage”: That, in two words, is what Air Force Space Command chief Gen. William Shelton says the U.S. military will gain from an international “code of conduct” on space activities that the State Department is now negotiating – in the face of intense skepticism from some key members of Congress. Shelton and other Pentagon space officials spent much of yesterday getting grilled by the Senate on the proposed code, which as currently drafted by the European Union might impede U.S. operations in space, according to an analysis by the Pentagon’s own Joint Staff. Today, at a breakfast with reporters, Shelton got a chance to say how the code might actually help the United States.

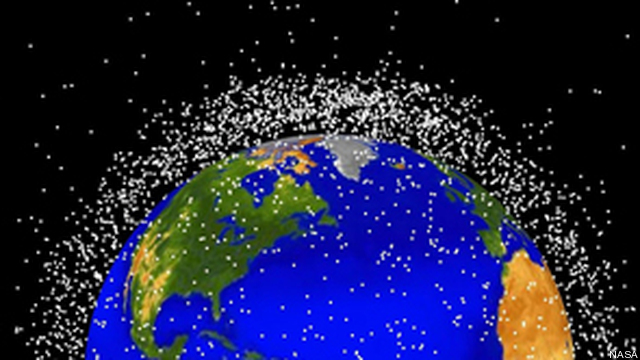

“The driver here is transparency,” Gen. Shelton said. “If you look at the volume of space, just the sheer volume of space from geosynchronous orbit down to the earth’s surface, that’s 73 trillion cubic miles. Now, the FAA has traffic control problems over the United States just watching air traffic [in a] fraction of 73 trillion cubic miles.” The U.S. military tries to keep tabs on everything in orbit, and it’s improving its already impressive capacity to do so: A tracking system now able to find items the size of a basketball will soon be able to find ones the size of a baseball, Shelton said. But even smaller objects – broken pieces of old satellites, debris from collisions or explosions, and so on – will still hit like a bullet at orbital speeds, potentially damaging expensive and delicate U.S. satellites. “There are hundreds of pieces you can track,” Gen. Shelton said. “There are tens of thousands of pieces you can’t track.”

When and if a properly written code of conduct is in place, however, participating nations would disclose what they were doing so everyone else would know where to look – easing the task of tracking systems – and what potential hazards to avoid – even if their sensors couldn’t see them at all. The code would also govern radio frequency interference and other potential problems with “safe passage” and operation in orbital space. “Trying to watch traffic in that search volume, it’s nigh on impossible,” Shelton said. “So tell me before you’re going to maneuver, tell me before you’re going to launch, tell me before you’re going to create some debris.”

Such transparent sharing of information “would be useful to everyone,” Gen. Shelton said. As a practical matter, though, it’s America that has the most at stake in space. The U.S. relies more than any other military on satellites to guide its smart bombs, to spy on adversaries, to keep troops in communication and able to call for help even when they’re a small unit on its own in the mountains of Afghanistan. China could afford to conduct its 2007 test of an anti-satellite weapon at such high altitudes that the debris will be around for decades; it’s not China’s essential military or commercial capabilities that would be at stake. China is unlikely to sign on to any code, but if other nations act more responsibly in space, the U.S. arguably has the most to gain.

Congress has its concerns about the code, however. Republicans in particular are typically uneasy about international pacts, which foreign countries can use to tie down the last superpower like the Lilliputians ganging up on Gulliver. But neither party is pleased with the idea that the Senate would not get to vote whether or not to ratify the code because it is not, technically, a binding treaty. “It may not be a treaty, but it will establish international norms,” said Sen. Ben Nelson, D-Neb., chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee’s panel on strategic forces, before Shelton’s testimony yesterday.

Nelson’s Republican counterpart, Alabama’s Jeff Sessions, went further. “I’m not sure you always gain a lot by formalizing written agreements,” he said at the hearing. “I’d like to be confident that the United States government, the Department of Defense, is not making commitments [which] will bind us and maybe make it impossible for us to effectively maintain our space and missile capability,” Sessions said. “We need to be able to dominate space.”

“It’s not legally binding and will not limit our ability either to develop systems or to defend ourselves,” responded Madelyn Creedon, the Pentagon’s assistant secretary for global strategy affairs, who formerly worked for the Senate Armed Services Committee as a staffer. “It’s not an arms control treaty… It will not ban space weapons,” she emphasized over and over. “One of the fundamental tenets of this discussion and the code of conduct would be the inherent right of self-defense reserved to every country.”

The U.S. certainly has its concerns about the current version of the code, Creedon said – and top officials have already pledged not to sign the European Union draft as-is. “The EU’s draft is a promising basis,” said Creedon, “but it’s just that, it’s just a starting point…. If we’re not successful as we go through the discussions over the course of the next year or so in negotiating a code of conduct that’s in our national security interest, then frankly we wouldn’t sign it.”

Pass a preemptive CR, deal with inflation and watch the debt limit: 3 tasks for Congress

John Ferrari and Elaine McCusker of AEI argue in this op-ed that Congress needs to act quickly to ensure American national security before getting bogged down in election season.