WASHINGTON: What homemade roadside bombs could do to Army and Marine ground vehicles was the ugly surprise of the last decade. What sophisticated long-range missiles could do to Navy aircraft carriers could be the ugly surprise of the next. “I think it would almost follow like the night to the day,” Rep. Randy Forbes told me in a recent interview. “The last decade… we asked a disproportionate sacrifice from the Army and Marine Corps,” he went on. “The next decade’s going to be the decade of seapower and projection forces, [and] some of those ugly surprises we see bits and pieces of already.”

As chairman of the House Armed Services seapower and projection forces subcommittee, Forbes wants to refocus fellow legislators, the Pentagon, and, for that matter, the media from a narrow debate over the troubled F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program to a wider look at all the capabilities that a carrier can support. That includes not just traditional manned fighters like the F-35, but also unmanned drones like the X-47B and the future UCLASS (Unmanned Carrier-Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike System), electronic warfare aircraft like the EA-18G Growler, and even cyber attacks.

The Navy’s top admiral seems to appreciate Forbes’s approach. The congressman is trying “to look at the whole package together,” and that’s helpful, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert said after a recent Senate hearing. “He’s saying, ‘we’ve got to think about all of this, are you?’ And I was telling him, ‘yeah.'”

The Navy is committed — albeit without great enthusiasm — to its variant of the Joint Strike Fighter for decades to come. But the sea service looks at the aircraft in context of what the Navy and Air Force are calling “AirSea Battle.” The prospective adversary, of which China is the archetype, would field an “anti-access/area denial” network, a layered defense of long-range sensors and missiles, potentially backed by manned aircraft and cyberattacks. In this fight, the F-35C provides stealthy manned strike against ground targets and air-to-air defense against enemy aircraft, as well as some cyber and electronic warfare capabilities, to complement the older and unstealthy F/A-18E/F Super Hornet. What those two manned fighters don’t bring to the carrier air wing’s table, however, is range. And as land-based missiles proliferate, both aircraft carriers and aerial refueling tankers will have to distance themselves ever further from the enemy.

“It’s not just the Chinese,” Forbes told me. North Korea, Iran, and Syria are putting in place some sophisticated anti-aircraft and anti-ship systems, he argued. Even the Lebanese militia group, Hezbollah, managed to cripple an Israeli corvette with a Chinese-built cruise missile in the 2006 war. (Admittedly, the corvette had turned its anti-missile defenses off). “The next decade is going to see a lot of countries with these weapons,” he said. “We should at least have a discussion and a debate about the assumptions we’ve always made that our carriers can operate pretty much wherever they wanted to.”

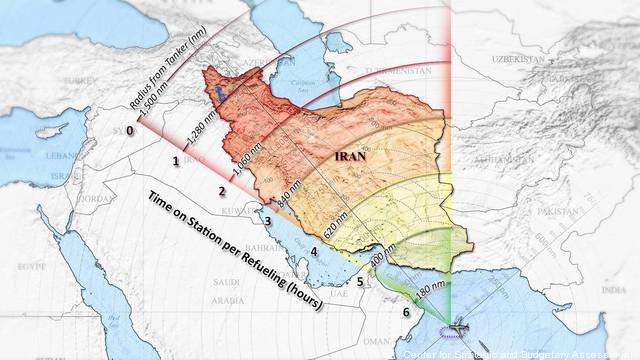

That presents a problem for the short-ranged fighters that the US spends most of its aircraft budget on. “F-18, F-35 are great platforms,” Forbes said, but studies from the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments predict that if future Navy carriers rely on those two aircraft alone, Forbes said, “we can only cover about a third of Iran and we can’t even get to China’s shore.”

“This is certainly not just an issue for the Navy,” said CSBA’s Mark Gunzinger, who’s written several studies on the subject. “It’s important for the Air Force to invest in new penetrating and long-range standoff,” i.e. bombers and long-range missiles. “It’s all about being prepared to operate in these higher-threat environments, which may early on in the conflict require increased range, increased persistence, increased survivability.”

Forbes was so struck by Gunzinger and company’s analysis that he had an aide hand out CSBA slides (the same ones in this article) at a recent hearing, otherwise dominated by the impacts of the sequester, where he asked Greenert about the range problem.

“The carrier air wing, Mr. Forbes, in my mind, is balanced,” the admiral answered. “We need range, we need payload, we need electronic warfare capability…and we need stealth.”

“Remember he had the range rings?” Greenert replied when I got to ask him about Forbes’s question, one week later. “You’ve got to get there and you’ve got to get back, so are you going to tank or do you have enough range [without mid-air refueling]? Two, you’ve got to get in wherever you’re going, [so] are you going to jam everybody or do you need to come in undetected — stealth or jamming?”

In both the hearing and their subsequent responses to my questions, both Greenert and Forbes emphasized the importance of the UCLASS, the carrier-launched armed drone. “You’re going to have some mix of the UCLASS to be able to deliver the range that you need,” Forbes told me.

The UCLASS is still more of an idea than an aircraft, and the Navy has repeatedly postponed issuing a formal request for proposals; Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) now says to expect an RFP for “preliminary design” in May. But a proto-prototype, the X-47B UCAS (Unmanned Combat Air System) will soon start test flights off an actual aircraft carrier, the first unmanned aircraft ever to do so. “When that happens, people will say ‘wow,'” Greenert said. “There’ll be a lot of pictures, and I think that will start a discussion.”

Even adding drones to the carrier air wing, though, does not complete the needed mix of capabilities. As both the US military and its adversaries become increasingly reliant on computerized sensors and wireless networks, some of the most dangerous things flying through the air may not be aircraft at all, but electrons.

WASHINGTON: What homemade roadside bombs could do to Army and Marine ground vehicles was the ugly surprise of the last decade. What sophisticated long-range missiles could do to Navy aircraft carriers could be the ugly surprise of the next. “I think it would almost follow like the night to the day,” Rep. Randy Forbes told me in a recent interview. “The last decade… we asked a disproportionate sacrifice from the Army and Marine Corps,” he went on. “The next decade’s going to be the decade of seapower and projection forces, [and] some of those ugly surprises we see bits and pieces of already.”

As chairman of the House Armed Services seapower and projection forces subcommittee, Forbes wants to refocus fellow legislators, the Pentagon, and, for that matter, the media from a narrow debate over the troubled F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program to a wider look at all the capabilities that a carrier can support. That includes not just traditional manned fighters like the F-35, but also unmanned drones like the X-47B and the future UCLASS (Unmanned Carrier-Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike System), electronic warfare aircraft like the EA-18G Growler, and even cyber attacks.

The Navy’s top admiral seems to appreciate Forbes’s approach. The congressman is trying “to look at the whole package together,” and that’s helpful, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert said after a recent Senate hearing. “He’s saying, ‘we’ve got to think about all of this, are you?’ And I was telling him, ‘yeah.'”

The Navy is committed — albeit without great enthusiasm — to its variant of the Joint Strike Fighter for decades to come. But the sea service looks at the aircraft in context of what the Navy and Air Force are calling “AirSea Battle.” The prospective adversary, of which China is the archetype, would field an “anti-access/area denial” network, a layered defense of long-range sensors and missiles, potentially backed by manned aircraft and cyberattacks. In this fight, the F-35C provides stealthy manned strike against ground targets and air-to-air defense against enemy aircraft, as well as some cyber and electronic warfare capabilities, to complement the older and unstealthy F/A-18E/F Super Hornet. What those two manned fighters don’t bring to the carrier air wing’s table, however, is range. And as land-based missiles proliferate, both aircraft carriers and aerial refueling tankers will have to distance themselves ever further from the enemy.

“It’s not just the Chinese,” Forbes told me. North Korea, Iran, and Syria are putting in place some sophisticated anti-aircraft and anti-ship systems, he argued. Even the Lebanese militia group, Hezbollah, managed to cripple an Israeli corvette with a Chinese-built cruise missile in the 2006 war. (Admittedly, the corvette had turned its anti-missile defenses off). “The next decade is going to see a lot of countries with these weapons,” he said. “We should at least have a discussion and a debate about the assumptions we’ve always made that our carriers can operate pretty much wherever they wanted to.”

That presents a problem for the short-ranged fighters that the US spends most of its aircraft budget on. “F-18, F-35 are great platforms,” Forbes said, but studies from the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments predict that if future Navy carriers rely on those two aircraft alone, Forbes said, “we can only cover about a third of Iran and we can’t even get to China’s shore.”

“This is certainly not just an issue for the Navy,” said CSBA’s Mark Gunzinger, who’s written several studies on the subject. “It’s important for the Air Force to invest in new penetrating and long-range standoff,” i.e. bombers and long-range missiles. “It’s all about being prepared to operate in these higher-threat environments, which may early on in the conflict require increased range, increased persistence, increased survivability.”

Forbes was so struck by Gunzinger and company’s analysis that he had an aide hand out CSBA slides (the same ones in this article) at a recent hearing, otherwise dominated by the impacts of the sequester, where he asked Greenert about the range problem.

“The carrier air wing, Mr. Forbes, in my mind, is balanced,” the admiral answered. “We need range, we need payload, we need electronic warfare capability…and we need stealth.”

“Remember he had the range rings?” Greenert replied when I got to ask him about Forbes’s question, one week later. “You’ve got to get there and you’ve got to get back, so are you going to tank or do you have enough range [without mid-air refueling]? Two, you’ve got to get in wherever you’re going, [so] are you going to jam everybody or do you need to come in undetected — stealth or jamming?”

In both the hearing and their subsequent responses to my questions, both Greenert and Forbes emphasized the importance of the UCLASS, the carrier-launched armed drone. “You’re going to have some mix of the UCLASS to be able to deliver the range that you need,” Forbes told me.

The UCLASS is still more of an idea than an aircraft, and the Navy has repeatedly postponed issuing a formal request for proposals; Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) now says to expect an RFP for “preliminary design” in May. But a proto-prototype, the X-47B UCAS (Unmanned Combat Air System) will soon start test flights off an actual aircraft carrier, the first unmanned aircraft ever to do so. “When that happens, people will say ‘wow,'” Greenert said. “There’ll be a lot of pictures, and I think that will start a discussion.”

Even adding drones to the carrier air wing, though, does not complete the needed mix of capabilities. As both the US military and its adversaries become increasingly reliant on computerized sensors and wireless networks, some of the most dangerous things flying through the air may not be aircraft at all, but electrons.

Jamming, Cyber, and the Great Convergence

The third leg of the future carrier aircraft trifecta, alongside manned fighters and armed drones, is electronic and cyber warfare to cripple enemy radars, radios, and networks. “Electronic attack is huge,” said Greenert, who’s written extensively on the subject (including for this website), in testimony before Forbes and his HASC colleagues. “[It’s] a major, major part of the air wing of the future, air warfare of the future, [all] warfare of the future, including cyber.”

“The electromagnetic spectrum, to me, is somewhere that we have fallen behind,” said Greenert. The US chose to under-invest in jamming in the 1990s “because we had no equal in that arena, and we were unchallenged. Well, we’re challenged today.”

The Air Force retired its last dedicated jamming aircraft over a decade ago, preferring to rely on stealth and on jamming pods for non-stealthy planes. The Navy and Marines, however, retained their seventies-vintage EA-6B Prowlers, which handle jamming for all the services. The Navy — but not the Marines — is now buying a new dedicated electronic attack plane, the EA-18G Growler, to replace the geriatric Prowler.

“It’s out of Schlitz,” Gen. James Amos, the Marine Corps Commandant, said of the Prowler in testimony to the House Armed Services Committee. In the near term, as Prowlers retire, the Marines are adding ground-based electronic warfare systems to help fill the gap, he said, “but I think the real replacement for us is the F-35B.” The Marines will develop an electronic warfare pod to augment their F-35s, Amos said, but even without such additional equipment — just using the plane’s standard built-in systems — an F-35B “has about, probably, 85 percent” of the capability of the latest Prowler.

The problem with that plan is that the Marines retire their last Prowler in 2019, while the F-35B squadrons are still building up.

“As we look forward to the F-35 coming into the inventory, there are a lot of capabilities we’ll be able to leverage… to offset the sundowning of the Prowlers,” said Marine Lt. Gen. Richard Tryon, Amos’s deputy commandant for plans, policies, and operations, at the Navy League’s Sea-Air-Space Symposium earlier this month.

“To be honest with you, I’m not as comfortable” with that approach, said Adm. William Gortney, who heads the Navy’s Fleet Forces Command, minutes later at the same event. “Controlling the [electromagnetic] spectrum is something we haven’t looked hard enough at in the last decade of war,” he said. “The question is, are we going to have enough capacity.” With the Prowlers going away and the F-35s still coming in, the Navy’s Growler squadrons will have to carry almost the entire burden of aerial jamming, not just for the Navy, but for all the armed services.

Such electronic warfare systems are only becoming more important as cyberspace becomes a battleground. The classic hacker operates over the Internet, but electronic warfare transmissions that once simply jammed an enemy’s radars and radios can now be used to insert viruses into his networks — including closed military systems that aren’t accessible online. Conversely, good old-fashioned jamming can defeat a wireless network just as effectively as a virus can, simply by disrupting transmissions between one node and the next.

“There is great convergence between the [electromagnetic] spectrum and the cyber world at the moment. That offers great opportunities,” said Vice Adm. Michael Rogers, the cryptologist who heads the Navy’s Fleet Cyber Command, at the Sea-Air-Space conference. “As a SIGINT [signals intelligence] guy… I just lick my lips.”

The military must not focus on cyber warfare in isolation, added Rear Adm. Michael Hewitt of the inter-service Joint Staff, but instead have “more of an integrated fires discussion, understanding how cyberspace can be an enabler.” If you want to shut down an enemy network, you can hack it, jam it or just blow it up, Hewitt explained to me after the Sea-Air-Space panel. The real power lies in the synergy of different techniques. “It doesn’t always have to be a cyber solution to a cyber problem,” he said. “We’re starting to grow out of that.”

The Navy needs a culture change, however, to fully realize this potential. The service still emphasizes “kinetic” solutions — i.e. destroying stuff — over electronic or cyber options, said Adm. Greenert at Sea-Air-Space. “If you’re going to study the Tomahawk Land Attack Missile and employ it on a ship, it’s a 40-week school” for young sailors, he said. For the standard shipborne electronic warfare system, the SLQ-32, “it’s a two-week school.”

The service also needs to sharpen its Cold War skills in hiding its radio and radar transmissions, what the military calls “emissions control” or EMCON. “The kids have got to understand the significance of it, because we haven’t looked at this for a generation,” Greenert told the conference. Meanwhile the number of electronic systems that emit a signal the enemy can track has grown exponentially. That makes warships vulnerable, even the vaunted aircraft carriers.

During one recent exercise aboard the USS Nimitz, Greenert said, “it took over an hour to get everything turned off.” Shutting down big emitters like the radar was one thing, but all sorts of smaller, unexpected signals kept showing up, “wi-fi’s, computers, you name it.” Over and over, Greenert recalled, officers would say, “What the hell is that? Turn it off.”

After that ordeal, however, the Nimitz crew kept working at shutting down all those tell-tale emissions, Greenert said, “and they got it down to about three minutes.”

That’s good news for the Navy’s number-one asset, the carrier force. “Carriers are going to be a very, very important part of our strategic makeup for a long time to come,” said Forbes. “Therefore we have to make sure we are guaranteeing their survivability to the largest degree possible, and we have to make sure they have the offensive capabilities to do what we need to do” — whether those capabilities are carried by manned aircraft, unmanned ones, or electrons.

Today, for example, carriers all deploy with a standard air wing, but that may not be adequate in the future. “It may very well be we have to look regionally and say we need different mixes in different portions of the world,” Forbes went on. A task force sailing to a low-threat region might make do with more Super Hornets, for example. One facing sophisticated anti-aircraft defenses might need more stealthy F-35Cs and radar-jamming EA-18Gs. One up against long-range anti-ship missiles might rely mainly on equally long-ranged UCLASS drones. And against the most sophisticated threats, the Navy might hold the carriers back and rely on missiles and drones launched from submarines.

“I don’t think we can afford NOT to have the carriers,” Rep. Forbes told me. “I think they’re still going to be vitally important to us. [The issue is] how we make them survivable.”

HASC adds Virginia-class sub, cuts F-35s in $849.8 billion draft defense policy bill

The bill sticks to budget caps laid out by the Fiscal Responsibility Act.