As Secretary of State John Kerry arrives in Ukraine, it looks as if the White House and Congress are likely to approve sending weapons there to help Ukraine drive out or destroy Russian troops and their proxies. James Kitfield spoke with a range of current and former intelligence and defense officials to examine the best ways to manage Russian President Vladimir Putin’s illegal invasion of a neighboring country and his hegemonic ambitions that appear to include “protecting” every Russian living outside the rodina. Read on. The Editor.

As a car drove a visiting American delegation through Kramatorsk in eastern Ukraine last month, former U.S. Ambassador to NATO Ivo Daalder was struck by the many national flags hanging in town squares and from private buildings and homes. Such a degree of national unity was a remarkable turnabout in a country whose divisions between a more European-oriented west and a Russian-speaking east were part of the psychic landscape. “That’s what [Russian President Vladmir] Putin has wrought with his invasion: he’s largely unified a fractious population of 40 million Ukrainians, the majority of which are mad as hell and now increasingly want to be part of the West,” Daalder said in an interview. Ukrainians have the will to subdue an ongoing, Russian-backed rebellion, he said, but not without urgent U.S. support and weaponry. Failing that, Putin is likely to dismember Ukraine with military force, establishing a precedent that Russia can ignore national borders and incorporate Russian-speaking populations it wishes to ‘protect.’

“We haven’t seen the likes of that doctrine in Europe since 1945,” noted Daalder. “Where does it end? In the Baltics? In Brighton Beach [New York]?”

Daalder is among a growing number of former and current U.S. officials who believe the crisis in Ukraine is fast reaching a fateful juncture. Daalder, James Stavridis, former Supreme Allied Commander of NATO; Michelle Flournoy, former Undersecretary of Defense; and Strobe Talbott, former Deputy Secretary of State all have come out in support of sending weapons to help Ukraine.

The view that America should for the first-time supply lethal weaponry to Ukraine is gaining traction within the Obama administration. When asked Wednesday if he favored supplying defensive arms during his Senate confirmation hearing Wednesday, presumptive Secretary of Defense Ash Carter replied, “I very much incline in that direction,” adding, “We need to support the Ukrainians in defending themselves.”

Current NATO commander Gen. Philip Breedlove also reportedly embraces the idea, according to The New York Times. HIs boss, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Martin Dempsey, is also reportedly open to the idea, as is Secretary of State John Kerry, who visits Kiev today.

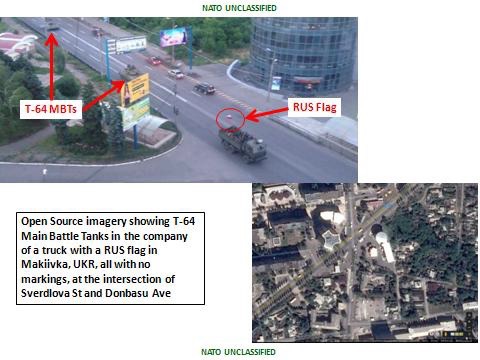

The calculus of U.S. officials has changed as a result of Russia’s December decision to send heavy weapons such as tanks, armored personnel carriers, artillery and advanced anti-tank guns. Unlike last summer, Moscow sent the convoys across the border in broad daylight, not even bothering to mask their origin and movement. The Russian reinforcements quickly joined a January rebel offensive that has captured the contested airport in Donestk, epicenter of the rebellion, and led to lethal shelling of Mariupol and other towns in the eastern Donbas province. On January 23, Aleksandr Zakharchenko, the leader of the self-proclaimed “Donetsk People’s Republic,” proclaimed that the separatist goal was now to seize the entire Donetsk oblast, a major step towards establishing a land bridge between Russia and Crimea, which Russia forcefully annexed from Ukraine last year.

“Putin has doubled down and upped the ante, making clear the he will not be dissuaded by Western economic sanctions that, along with falling oil prices, already have put a significant strain on the Russian economy,” Nicholas Burns, former U.S. Ambassador to NATO and number three at the State Department, said. As long as Moscow and the pro-Russian rebels believe they have an uncontested road to Crimea through eastern Ukraine, he said, they have no incentive to stop and negotiate.

“What Vladmir Putin has done first in Transnistria [Moldova in the early 1990s], in Georgia [in 2008], and now in Ukraine, is to use brute military force to destabilize its neighbors, which is not only a serious violation of international law, but also a direct strategic challenge to the West,” said Burns, director of the Future of Diplomacy Project at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. “The United States and its allies need to show strength now and exact a cost for Russian actions in Ukraine, or else Putin may come to doubt the level of our commitment to NATO allies in the region such as Latvia and Estonia, which also have large Russian-speaking populations.”

Stumbling Towards War

From the very beginning there was something deeply troubling about how the West and Russia stumbled into the Ukrainian conflict, the worst crisis in their relations since the Cold War ended. It began as a relatively picayune disagreement over trade pacts. In February 2014 Putin was distracted by hosting the Winter Olympics in Sochi. Months before, European Union diplomats had gotten into an unexpected tug-of-war with Putin over the orientation of Ukraine by offering notoriously corrupt Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych an EU “association agreement” and loans to bailout his nearly bankrupt economy. Putin won the bidding war by offering Yanukovych $15 billion to instead join his Eurasian Union, an attempt by Putin to surround Russia with compliant trading partners beholden to Moscow.

When violent street protests in Kiev forced Yanukovych to flee for his life in February 2014, Putin felt aggrieved. Ukraine had been bought and paid for, in his mind. In short order Russia military forces grabbed Crimea, home to Russia’s Black Sea fleet. Russian supported rebels in eastern Ukraine also seized government buildings and occupied a large portion of the eastern province of Donbas.

When a new government in Kiev launched a counteroffensive last summer to defeat the rebels, Russia upped the ante, sending convoys of heavy weapons and Russian “volunteers” into eastern Ukraine. The quickly outgunned Ukrainian military reportedly lost well over half of its deployed tank and armor forces. In desperation, new Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko signed a ceasefire agreement designed to freeze the conflict in place until a negotiated settlement could be reached. It didn’t hold. Since the fighting resumed, Russian-backed rebels have seized an additional 500 square kilometers of territory.

As the ceasefire broke down the United States and European Union imposed tougher sanctions. Coupled with a precipitous drop in world oil prices, the sanctions have caused the Russian ruble to lose over half its value, sparking the worst currency crisis in Russia since Moscow defaulted on its debt in 1998.

Even as the ruble collapsed, Putin’s popularity soared. Anti-western propaganda in the largely state-controlled media has stoked Russian nationalism, and Putin’s approval ratings have lingered in the stratosphere above 80 percent throughout the crisis.

Escalation Dominance

What troubles some experts about the Ukraine crisis is a phenomenon called “escalation dominance.” The term was coined by U.S. military and national security experts who developed the strategy of deterrence during the Cold War. The concept holds that the United States can best contain conflicts and avoid escalation if it is dominant at each successive rung up the “ladder of escalation,” all the way to the top rung of nuclear weapons. Such a doctrine, based in balance-of-power calculations, is important because that’s how former KGB operative Vladimir Putin and his tight circle of military hardliners and spies seem to think.

As the Obama administration and European allies have responded to Russian provocations with ever tighter economic sanctions, they have capitalized on their escalation dominance in the economic sphere. The Russian economy is increasingly isolated and all but crippled. Yet Putin continues to escalate the crisis militarily to applause from a majority of Russians, because he has taken the measure of NATO and apparently decided that in the military sphere at least he has escalation dominance.

“We seem to have forgotten that even a weaker state with much more at stake in a given region and conflict can have ‘escalation dominance’ far out of proportion to its relative power, and that’s especially true if it’s a major nuclear weapons state like Russia,” said Dmitri Simes, president of the Center for the National Interest and a Russian expert. Those who advocate supplying Ukraine with lethal weapons hope to increase Russian casualties and raise the pain for Putin until he backs down and abandons the rebels, he notes, but it could very well have the opposite effect of provoking Putin to double down once again and escalate the military crisis further. “The West needs to understand that this is a very dangerous situation that could turn Russian into a hostile nuclear power for the foreseeable future, and lead to nuclear brinksmanship every bit as dangerous as the Cuban missile crisis.”

Military Brinksmanship

In case Western leaders and militaries have missed that message, the Russian military has worked hard to remind them that continued escalation could have consequences far beyond Ukraine. A recent report by the London-based think tank, the European Leadership Network, detailed no less than 39 “highly disturbing” incidents of close military encounters between Russian and NATO forces in the past eight months.

Senior Russian officials have reportedly threatened to put the Russian nuclear arsenal on high alert, and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov claims that Moscow has every right to deploy nuclear weapons to the recently annexed Crimea peninsula.

Of course, a U.S. decision to supply lethal weaponry to Ukraine does not run counter to the doctrine of escalation dominance. It would arguably increase U.S. and Western leverage at this rung of the Ukrainian conflict, hopefully leading to a negotiated settlement by raising the costs of Russia’s actions there. A similar calculation was made in the early 1980s when the United States decided to arm the Afghan mujahedeen who were trying to repel a 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The fear then was that the Soviets would escalate by invading Pakistan, where the Afghan rebels were armed and trained by the CIA. The Soviet Union decided to withdraw its troops rather than escalate, presaging the dissolution of the Soviet empire a few years later.

Vladimir Putin has called that breakup of the Soviet Union the “greatest geopolitical tragedy of the twentieth century,” and he seems to be in a gambling mood. The question confronting Western leaders is how far he is willing to go in order to reclaim a sphere of influence and strategic buffer zone in Russia’s “near abroad.” Faced with mounting casualties in Ukraine and a slumping economy, will Putin escalate? Might he try to sow instability along NATO’s exposed eastern flank in the Baltics, which is defended by little more than tripwire forces meant to signal alliance resolve where little exists?

“I support arming the Ukrainians, but only if we’re going to flood the zone with enough weapons to make a difference in the fighting there,” said retired four-star Gen. Barry McCaffrey, a decorated combat veteran who spent much of his career in Europe. “Because so far NATO’s reaction to Putin’s aggression has been to send a handful of forces to the Baltics to demonstrate ‘resolve,’ which has only convinced Putin that the alliance is either unable or unwilling to fight. So we had better change his calculus pretty soon, and contest Putin’s stated doctrine that he is willing to intervene militarily in other countries to ‘protect’ Russia-speaking people. For God’s sake, the last time we heard that was just before Hitler invaded the Sudentenland.”

No service can fight on its own: JADC2 demands move from self-sufficiency to interdependency

Making all-domain operations a warfighting capability means integrating, fusing, and disseminating a sensor picture appropriate for a particular theater segment, not all of them, says the Mitchell Institute’s David Deptula.