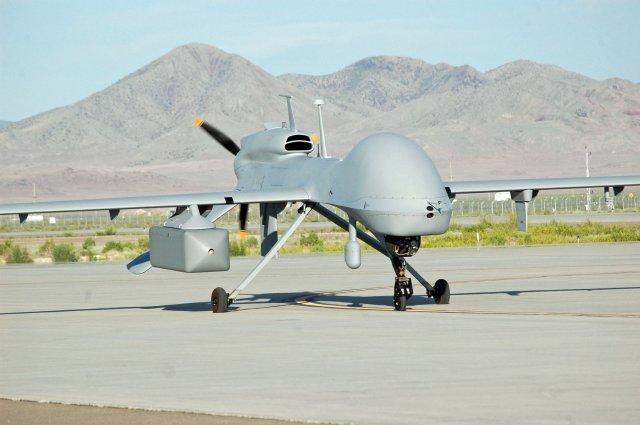

An Army Grey Eagle testing a NERO jammer.

PENTAGON: The US Army is struggling to fund the increasingly crucial capabilities it fields for electronic warfare, which it largely abandoned after the Soviet Union fell. The Army has over 32,000 short-range defensive jammers to stop roadside bombs, but on current plans, it won’t have an offensive jammer until 2023.

“Can that be accelerated? Yes,” said Col. Jeffrey Church, chief of electronic warfare on the Army’s Pentagon staff. “Technology exists today that does a lot of things that we would like MFEW [the Multi-Function Electronic Warfare system] to do,” he said, some of which the Army could even buy commercially.

Col. Jeffrey Church

But with the Army downsizing more than any other service and sequester in the offing, “there’s no money tree,” Church told me in an interview. “So if you’re going to grow a robust electronic warfare program, who’s going to pay for that?”

So what’s the current state of Army electronic warfare today? “I have doctrine. I have people. I have facilities,” said Church. “What we lack is the materiel.

“If you go to a unit today in the Army and you say, let me see your ‘electronic warfare equipment,’ and you go to the EWO (Electronic Warfare Officer) and he opens up his wall locker, it’s empty,” Church said. “Right now the Army relies on borrowing assets from other people,” such as Navy’s Growler aircraft.

“Our senior army leaders have known and do know that electronic warfare is something the Army must have,” said Church, who’s also the senior of the Army’s 813 electronic warfare personnel. (That the most senior EWO is a colonel, not a general, shows how new the field is). “It’s a matter of resource prioritization and where do you fall in those priorities.”

Where does electronic warfare fall? The Pentagon budget for fiscal 2016 includes $2.5 million — a rounding error for a major weapons program — for something called the Electronic Warfare Planning & Management Tool. Entering service in September 2016, EWPMT is much-needed software that will let electronic warfare troops pull together data from sensors — such as Navy Growlers — and Army’s DCGS-A intelligence network.

“EWPMT is what allows them to see the battlefield in the electromagnetic environment,” Church said, “so you’ll be able to tell your commander, ‘this is where we have interference. This is where we are. This is where the enemy is. I don’t know what that is, but I’m getting some kind of signal.”

Electronic Warfare Planning & Management Tool, EWPMT (Army concept)

But EWPMT is currently a command-and-control system with nothing to command and control. The 32,000 CREWS jammers that protect Army vehicles from roadside bombs are powerful at short range, but they’re not linked to any kind of network, so EWPMT can’t use them as a source of data, let alone control them. The Army has only a handful of longer-range systems, bought with emergency funds and/or rapid equipping authorities for the specialized circumstances of Afghanistan and Iraq.

“We got good technology into the field to save soldiers’ lives,” Church said. “We didn’t get any programs of record, so we don’t have budgets, we don’t have base dollars.”

The Multi-Function Electronic Warfare system is supposed to fix that. MFEW will be a network of sensors and jammers mounted on drones of various sizes, ground vehicles from Humvees to heavy trucks, fixed sites, soldiers’ backpacks, and potentially, helicopters as well.

In contrast to the single-purpose platforms of Cold War electronic warfare units, MFEW won’t require a dedicated vehicle to carry it, Church emphasized: The Army can’t afford it, he said, and modern miniaturized electronics don’t require it. Instead, MFEW will hitchhike on ground vehicles going about their normal missions, feeding data to and getting orders from Army electronic warfare officers back at the command post. On drones, MFEW will be just another plug-and-play module to use or not according to the mission, as many specialized sensors already are.

How close is this vision to reality? “Right, now MFEW is not a program,” said Church, which limits the Army’s ability to fund it. Currently, MFEW is a “concept” caught up in the often-grueling process of becoming a formal Army requirement. “We’re on about the fifth rewrite of the MFEW CDD (Capabilities Development Document),” Church said. Once that CDD is completed and approved, MFEW can become a program of record and receive base budget dollars.

MFEW is scheduled to enter service in 2023 and reach full operational capability (FOC) in 2027. Until then, we’re playing catch-up.

“Guys like the Russians, guys like the Chinese, their surrogates, they’ve spent the last 20 years continuing the development and acquisition of an electronic warfare capability, whereas… the Army got out of the business,” Church said. When the field was revived, he said, “Army electronic warfare started from nothing, and it started from nothing in a combat environment where a lot of US soldiers were being killed or wounded due to the radio-controlled IED.”

Today we handle radio-controlled roadside bombs very well indeed, Church said: “Now we have to take this to the next level, and MFEW is the next level.”

Of course, all this is going on while the senior leadership at the Pentagon reviews its electronic warfare portfolio. The recently created Electronic Warfare Programs Council is the place; it’s headed by Frank Kendall, the undersecretary for acquisition, technology and logistics, and the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Adm. James Winnefeld.

Norway’s top officer on his ‘biggest challenge,’ next frigate and new NATO neighbors

Gen. Eirik Kristoffersen, Norway’s Chief of Defense, talks to Breaking Defense about his plans for spending on new frigates and subs, the challenges of upgrading Norway’s “digital backbone” and refilling the military’s stocks.