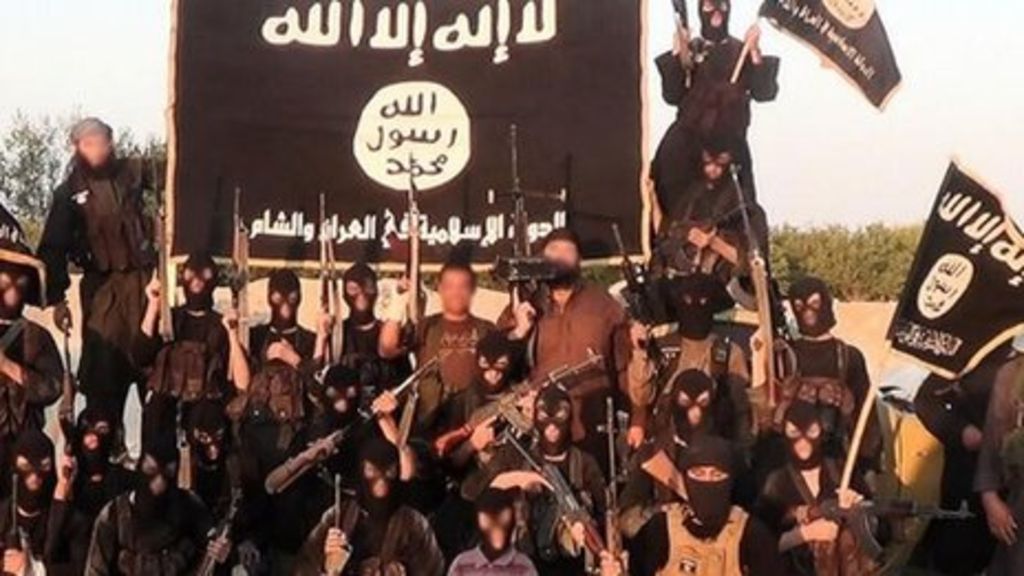

Daesh fighters

Sen. John McCain said in early February that, it “is time for the international community to abandon the absurd fiction of a political solution that leaves Assad in power (in Syria).” McCain, who was reacting to Amnesty International’s report about mass executions by Bashar al Assad’s regime, argued: “Bashar Assad does not belong in a palace in Damascus. He belongs in a jail cell in The Hague.”

Less than two weeks later, the Pentagon is apparently considering sending U.S. ground forces into Syria—not to depose Assad—but to take on Daesh (aka ISL). According to one defense official, “It’s possible that you may see conventional forces hit the ground in Syria for some period of time.”

Charles V. Pena

This is a nexus of two equally bad ideas: regime change and unnecessary military intervention in another Muslim country.

To begin, U.S. policymakers should recognize by now that regime change doesn’t work. Certainly, we have used military force to successfully depose regimes: the Taliban in Afghanistan, Saddam Hussein in Iraq, and Muammar Gaddafi in Libya. Given relatively weak opponents, achieving initial military victory is not really the concern. But the envisioned result — a peaceful, stable, democratic state — has not been achieved. That much is more than obvious in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Why Senator McCain believes the outcome in Syria would be different defies logic.

The problem with regime change is that it requires unconditional surrender and the willingness of those who surrendered to pursue a peaceful path to democratic stability. That was the case in post-World War II Europe and Japan. But the Middle East consists of countries divided along religious, ethnic and tribal lines with a long history of conflict that is not easily reconciled.

Worse yet, an outside force seeking to impose its will becomes an all too-easy target for the various factions to focus on as the immediate enemy.

More important, deposing odious rulers who commit atrocities — often a key justification used to argue for regime change — is an insufficient rationale for using U.S. military force. The primary and overriding criteria for putting the military in harm’s way should be when U.S. national security is directly at stake. That was the case in Afghanistan for initial U.S. military action in the wake of 9/11 because the Taliban regime provided safe harbor for Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda. However, Afghanistan has long since become a futile exercise in nation-building unrelated to U.S. national security.

There is no question Bashar al Assad is a threat to his own people — Syrians who oppose him. But however brutal and unsavory, the regime in Damascus is not a direct threat to U.S. national security. Syria has no military capability to inflict harm on America. And to the extent that U.S. military forces could be threatened by the Syrian military, it’s only because we have forces in the region within range of their weapons.

But what about Daesh? Isn’t Daesh a threat? Yes, it is a threat in Iraq and Syria because that is where Daesh is trying to establish a caliphate based on its radical vision of Islam. But the group is not an existential threat to the U.S. Therefore, it is primarily up to the Iraqis, Syrians, and others—such as the Turks and Gulf States—in the region to combat Daesh. After all, they have more at stake and the most to lose by letting Daesh gain a stronghold. And the reality is that that’s exactly what is happening. The fight against the terror group is being waged by a loose coalition comprised of Iraq; Shiite militias; Turkey; the Kurds; Saudi Arabia; smaller Gulf nations like the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and Oman; and Jordan. We need more of that, not more U.S. boots on the ground.

We must recognize that the threat that Daesh really represents is the struggle within Islam. First and foremost, Daesh is at war with its fellow Muslims who do not agree with and do not want to live by their radical version of Islam. Sending U.S. troops into Syria would only put them in the middle of someone else’s civil war, making them a target.

Moreover, Daesh represents one form of radical Islamic ideology. So killing members of Daesh — which is sometimes necessary — is really just tactical and not a strategic solution.

It’s important to remember Daesh’s roots: The U.S.-led invasion of Iraq created the conditions in 2004 for the rise of al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) — an even more radical version of al Qaeda — founded by Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. AQI split from al Qaeda in 2014 over a disagreement about merging with another group—the al Nusra Front—and became Daesh.

So it may be possible to “destroy ISIS” as President Trump wants, but it will likely be followed by yet another radical Islamic group.

Indeed, U.S. boots on the ground in Syria will likely only fan the flames of radical Islam. It would be yet another military intervention in a Muslim country — Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya — that would confirm the al Qaeda and Daesh radical Islamic narrative that the U.S. is waging a war against Islam. And any U.S. military action will inevitably result in collateral damage—no matter how carefully and precisely we target the enemy. The resulting deaths of innocent civilians would give Muslims more reasons to hate America.

This is especially important if we are concerned about radicalization of Muslims as a terrorist threat to America. For example, the Orlando Pulse nightclub shooter—Omar Mateen, who had pledged his allegiance to Daesh without any training, instruction, or direction connection to the group — told a police negotiator, “You have to tell the U.S. government to stop bombing. They are killing too many children. They are killing too many women.”

So whether it’s for regime change or Daesh, U.S. military involvement in Syria is beyond a bad idea. Just say no.

Charles V. Peña, former director of defense policy studies at the Cato Institute, is a senior fellow with the Defense Priorities thinktank. Peña is the author of Winning the Un-War: A New Strategy for the War on Terrorism. Follow him on Twitter @gofastchuck.

Sullivan says Ukraine supplemental should cover all of 2024, long-range ATACMS now in Ukraine

“We now have a significant number of ATACMS coming off their production line and entering US stocks,” Jake Sullivan said today. “And as a result, we can move forward with providing the ATACMS while also sustaining the readiness of the US armed forces.”