WASHINGTON: Raytheon is developing a next-generation version of the venerable TOW anti-tank missile. Its range will be almost 50 percent greater than the current TOW 2B and twice that of the original model introduced in 1970. And it will likely boast a new fire-and-forget option will allow the missile to guide itself to the target without a human gunner steering it.

With this and other improvements, the Army plans to keep the TOW family in service into the 2050s. That’s eight decades after its introduction, a lifetime comparable to the Army’s CH-47 Chinook helicopter and the Air Force’s B-52 bomber. In fact, the TOW missile was mandatory equipment for the original version of the Army’s future replacement for the M2 Bradley, the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle. While the service is now rebooting OMFV with all options on the table, Raytheon is still aiming to deliver the next-gen version on the original timeline, 2025-2026.

An early-model TOW missile launcher. (Redstone Arsenal photo)

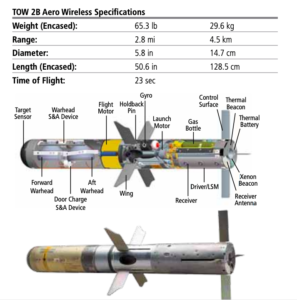

Like the parable of Lincoln’s axe, every part of the TOW has been upgraded and replaced since the early days. Of the many variants currently in service, the latest anti-tank model, the TOW 2B, already has a 4.5 kilometer (2.8 mile) range, compared to 3 km (1.9 miles) for the original model, and a completely different warhead. The original TOW impacted directly on an enemy tank’s armor and exploded, using the shaped charge effect to blast through armor. Such warheads proved so devastating to traditional steel plate that both the Soviet Union and the West invested massively in multi-layered composite armors combining different materials to diffuse the blast. So, now, the TOW 2B flies over the target and then detonates above it, the explosion creating slugs of molten metal – known as Explosively Formed Penetrators – that rip at high velocity through the vulnerable top armor.

The next upgrade, Raytheon experts told me, is to replace the rocket. An entirely new rocket motor and improved aerodynamic design will carry the warhead more than 6.5 km (four miles), significantly shortening time to impact at shorter ranges in the process.

US Army M2 Bradleys fire TOW anti-tank missiles during a training exercise in Germany.

Meanwhile Raytheon is also improving the guidance system. Originally TOW referred to how the missile spooled a control wire behind it – a towed wire, as it were – that let the operator fly it precisely to the target like a plane. The official (contrived) acronym is “Tube-launched, Optically tracked, Wire guided.” Nowadays the “W” stands for “wireless,” because ever since 2009, the more modern versions dispense with the physical wire.

Even so, a human being still has to fly the TOW to the target. That’s a feature the Army actually likes for a lot of situations. It allows the high precision of a trained human gunner and a manual override if the original target was misdesignated, a crucial feature in counterinsurgency conflicts with civilians on the battlefield and strict rules of engagement. But it also potentially exposes the human gunner to enemy fire if the target or its teammates see or hear the missile launch and calculate where it’s coming from. Future generations of TOW won’t take away the option for human control, but they could add an autonomous mode where the human operator can designate a target, fire, and then get under cover while the missile guides itself.

We spoke to three Raytheon executives about the ongoing effort to upgrade the TOW:

- Sam Deneke, VP for Land Warfare Systems, who’s spent 20 years with Raytheon as an engineer and program manager;

- Breanne Escalante, the program director for TOW, whose 14 years with Raytheon include work on a wide range of weapons from the Tomahawk cruise missile to the air-to-air AMRAAAM; and

- Ed Dunlap, business development lead for TOW, who joined the company in 2004 after 24 years in uniform. A retired Marine Corps lieutenant colonel, Dunlap learned to love the TOW first in training and then in combat during Operation Desert Storm.

Let’s hear from them in their own words (edited for clarity & brevity):

Ed: I’m a retired Marine Corps armor officer. Marine tank battalions had TOW companies in them back when I was on active duty. I was a tank company commander during Desert Storm, I had a TOW section attached to me, and they did great.

It was a huge asset. It was a force multiplier that we’d put into all of our plans. For example, I was an M60A1 tanker, so I did not have thermal sights on my vehicles, but the TOW systems came with the thermal sight that allowed them to see where I couldn’t, and they provided some great overwatch and some great engagements for me.

I still have friends out there that are on active duty that use a TOW system.

A Humvee fires a TOW missile.

Sam: I think we’re justifiably proud of the rich history of the TOW missile as we’ve been producing it over the decades. In 2019 we celebrated delivery of the 700,000th TOW missile out of Tucson facility here in Arizona. But we’re equally excited about the work we’re doing to evolve the capabilities of the TOW missile in the future.

Obviously the warhead and the attack path of the TOW 2B is vastly different from what we were talking about in the 70s and 80s. The 2B is a fly-over, shoot-down version of the missile.

Ed: It actually flies over the target, senses the target, and then fires [explosively formed penetrators]] down to the top of the tank, the most vulnerable portion of the tank.

[Editor’s note: This is different from the Javelin, also a Raytheon “top attack” anti-tank missile – with Javelin, the warhead itself impacts the top armor of the target.]

Sam: The US Army has been very public, saying that TOW will be in inventory at least through the year 2050, and it’s also been very supportive of continued development.

Breanne: TOW’s got a rich history, but it also has great life going forward. In fact, we’re currently under contract from Combat Capabilities Development Command’s Aviation and Missile Center to provide three demonstrations for extended range on TOW in the fourth quarter of next year.

That really is the precursor to the next generation of TOW. It’s going to greater than six and a half kilometers.

Ed: We were originally at 3.75 km, it evolved to a 4.5 kilometer missile today, and we are working on evolving to greater than 6.5 kilometers. We are putting a different propulsion package into the missile, and we’re making some aerodynamic changes and some other changes that enable us to fly further in a shorter time.

Q: Will you develop a non-line of sight version – a weapon that the operator can shoot at targets they can’t see themselves, but that are spotted by some kind of drone or remote sensor?

Ed: The extended range missile that we’re working on now would lead to future growth, but right now there’s no plans on going into a non-line of sight system.

Schematic and specs for one of the latest TOW models. (Raytheon graphic)

Breanne: What’s key here is that the user really likes the fact that we have command line of sight, so you’re really able to shoot and track that missile exactly where you want to go. And they’ve in fact been maintaining that capability as we try to move forward to being able to potentially integrate fire-and-forget as well.

Ed: Command line of sight does allow positive control of the missile all the way to the target in cases where rules of engagement are strict. But additionally, as part of the contract for extended range, we anticipate that will also shorten the time of flight to targets within the most normal engagement ranges, three thousand to four thousand meters, where most direct fire engagements happen.

As Breanne mentioned earlier, we are on the contract with CCDC on a Defense Ordnance Technologies Consortium contract to deliver, by the fourth quarter next year, three extended-range missile prototypes. That technology will transfer into what we’re calling the TOW Kilo program, which would eventually turn what we developed during this current contract into a qualified and producible missile.

That program would support the 2025-ish timeframe we originally were working towards providing the new missile to the first unit equipped with OMFV. That slipped some, but we’re still working towards the original schedule: 2025, 2026.

Under the original request for proposals, in the requirements for the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle, TOW was designated as the multipurpose guided missile for that system. In other words, offerers had to be able to explain how they were going to integrate the TOW [on their OMFV designs]. We’re hoping as the army reassesses and looks at the requirements, that will remain.

Q: Whatever happens with future vehicles, will the new missile be compatible with all the old launchers, for example on M2 Bradleys, and the portable version in infantry units?

Sam: Certainly. One of the principal design tenets that we have is maintaining that backwards compatibility for all of our US users and almost 40 international customers. They’d be able to use the extended range missile with whatever version of the launcher that they have, either dismounted or mounted.

Ed: Absolutely. Our focus is on providing these enhanced capabilities to US forces, but we want to maintain our international market and get the extended range TOW out there to our allies as well.