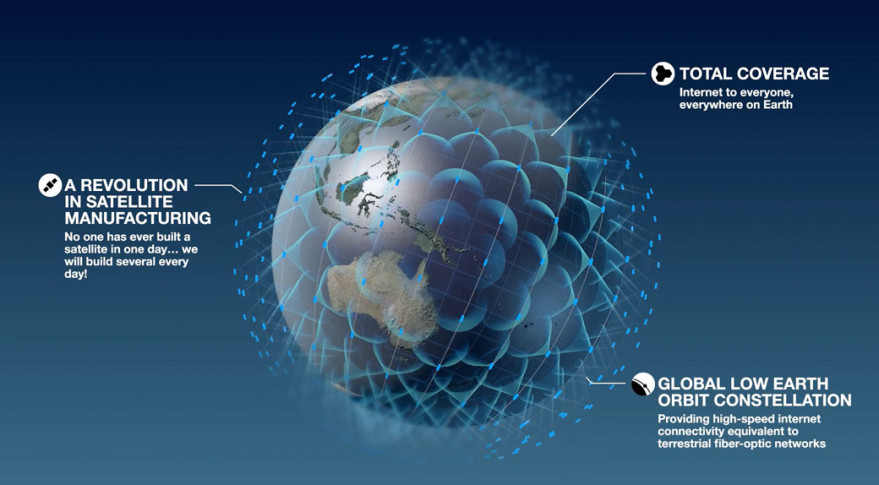

OneWeb mega-constellation (OneWeb)

WASHINGTON: Operators of commercial broadband mega-constellations in Low Earth Orbit, known as p-LEO providers, have until Thursday to respond to Space Force’s draft request for proposals (RFP) on how it might acquire their services. Space Force’s goal is to expand the options for military users in the field to connect to the internet, and share data including video.

“This approach would pave the way for LEO constellations like OneWeb’s network both to support coordinated control of the battlespace and to supply hosted solutions to the armed forces. … We are excited to see this draft lead to a final RFP,” said Dylan Browne, head of government business at OneWeb, one of the firms with eyes on a potential contract.

Brown added that OneWeb’s satellites are “well positioned” to meet Space Force’s needs, “given our planned network’s inherent resilience, its interoperability with GEO Ku-band networks, and its scalability, which makes it able to handle simultaneous usage surges in places around the world.”

OneWeb on Sept. 15 successfully added 34 satellites to its constellation, bringing the total number in orbit to 322 satellites — almost half the planned 648 birds planned. According to the company, it remains on track to start actual broadband services this year, and achieve global service coverage in 2022.

Similarly, SpaceX is populating LEO with its Starlink constellation, which ultimately is planned to comprise some 100,000 satellites. As of its last launch on Sept. 14, the company has orbited 1,791 Starlinks and has approval in 14 countries to operate. Like OneWeb, SpaceX is not yet actually offering commercial services.

However, it has been participating in a number of DoD experiments and prototypes, including the Space Development Agency’s effort to build new missile tracking satellites in lower orbits than the current Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS) birds.

The p-LEO draft proposal is not public but only only available to industry upon contacting Space Systems Command (SSC) — the new Space Force command for acquisition, replacing Space and Missile Systems Center, at Los Angeles AFB. The SSC request for information (RFI) says that Space Force intends to grant indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity (ID/IQ) contracts to a number of p-LEO providers.

Commercial Space Acquisition

DoD for many years has had, in one form or another, a program to tap into commercial satellite communications (SATCOM). Currently, use of commercial bandwidth is managed by SSC’s Commercial Satellite Communications Office (CSCO), headed by Clare Grason — an office that Space Force is looking to expand to handle acquisition of other types of commercial space capabilities, such as remote sensing.

CSCO serves as a middleman between commercial satellite operators and then matches the needs of various operational commands and other DoD customers to a provider — helping manage the contracting process. However, CSCO doesn’t have a budget or program of record for buying bandwidth access; rather funds are found in the Overseas Contingency Operations fund when a need for a surge in connectivity is required by operators.

Chief of Space Operations Gen. Jay Raymond, in his February 2020 Enterprise SATCOM Vision document, laid out a farther reaching aspiration.

That document calls for Space Force to build and manage a seamless network of military and commercial comsats in all orbits, accessible to troops, vehicles, ships and aircraft via ground terminals and mobile receivers that would automatically “hop” from one satellite network to another. It includes looking at new acquisition approaches, and Space Force has been experimenting with using contracting authorities like Section 804 and Other Transaction Authority (OTA).

Whither ‘Satellite As A Service’?

But traditional commercial SATCOM providers — whose satellites are based in higher Geosynchronous Orbits (GEO, some 36,000 kilometers in altitude) or Medium Earth Orbit (MEO, between GEO and the edge of LEO at some 2,000 kilometers) — continue to be disappointed with the lack of progress toward that goal.

Major industry players, including Viasat; Hughes; Intelsat; Inmarsat; SES and Eutelsat, have been arguing the Pentagon would save money, and speed capabilities, by buying satcom “managed services” — like an average mobile phone or cable TV/Internet plan — instead of leasing commercial bandwidth in fits and starts for short periods of time.

“If the Space Systems Command is going to acquire other commercial services in the same fashion that CSCO has been acquiring commercial SATCOM, then that will not serve the warfighter well. As you know, we have been advocating for many, many years now that commercial SATCOM be acquired more strategically, and not on an ad hoc, case-by-case, reactionary basis,” said Rebecca Cowen-Hirsch, senior vice president for government strategy and policy at Inmarsat, in an interview. “If today’s method is going to apply to other broadband commercial services, then that is a recipe that is not going to bake well.”

“We’ve been talking about it for as long as I’ve been involved with satellites in the last 12 years,” Rick Lober, vice president of Hughe’s Defense & Intelligence Systems Division, told Breaking Defense. “We need to see this stuff move more towards programs of record, and not, you know, BAAs, OTAs, studies, prototyping, and that seems to have been been slow.”

Congress, too, has been trying to push the Department of the Air Force, which oversees Space Force and the Air Force, and DoD writ large to reform how it buys commercial bandwidth. Lawmakers have been consistently adding money to launch a program of record to buy SATCOM as a service for a number of years.

“There’s a trail that goes back to 2014,” Hirsch noted. “And it is a bipartisan issue.”

Space Force asked for $23.8 million in its fiscal 2022 budget request, but that was for integration of commercial SATCOM into its portfolio of options for bandwidth — not for actually buying data and/or services from companies.

“And that’s an M as a million, so it’s a very infinitesimally small number in the big scheme of things,” Cowen-Hirsch said. She noted, with some obvious frustration, that commercial SATCOM providers keep waiting to see actual movement rather than “just acquiring additional consultants to do studies.”

HASC chair backs Air Force plan on space Guard units (Exclusive)

House Armed Services Chairman Mike Rogers tells Breaking Defense that Guard advocates should not “waste their time” lobbying against the move.