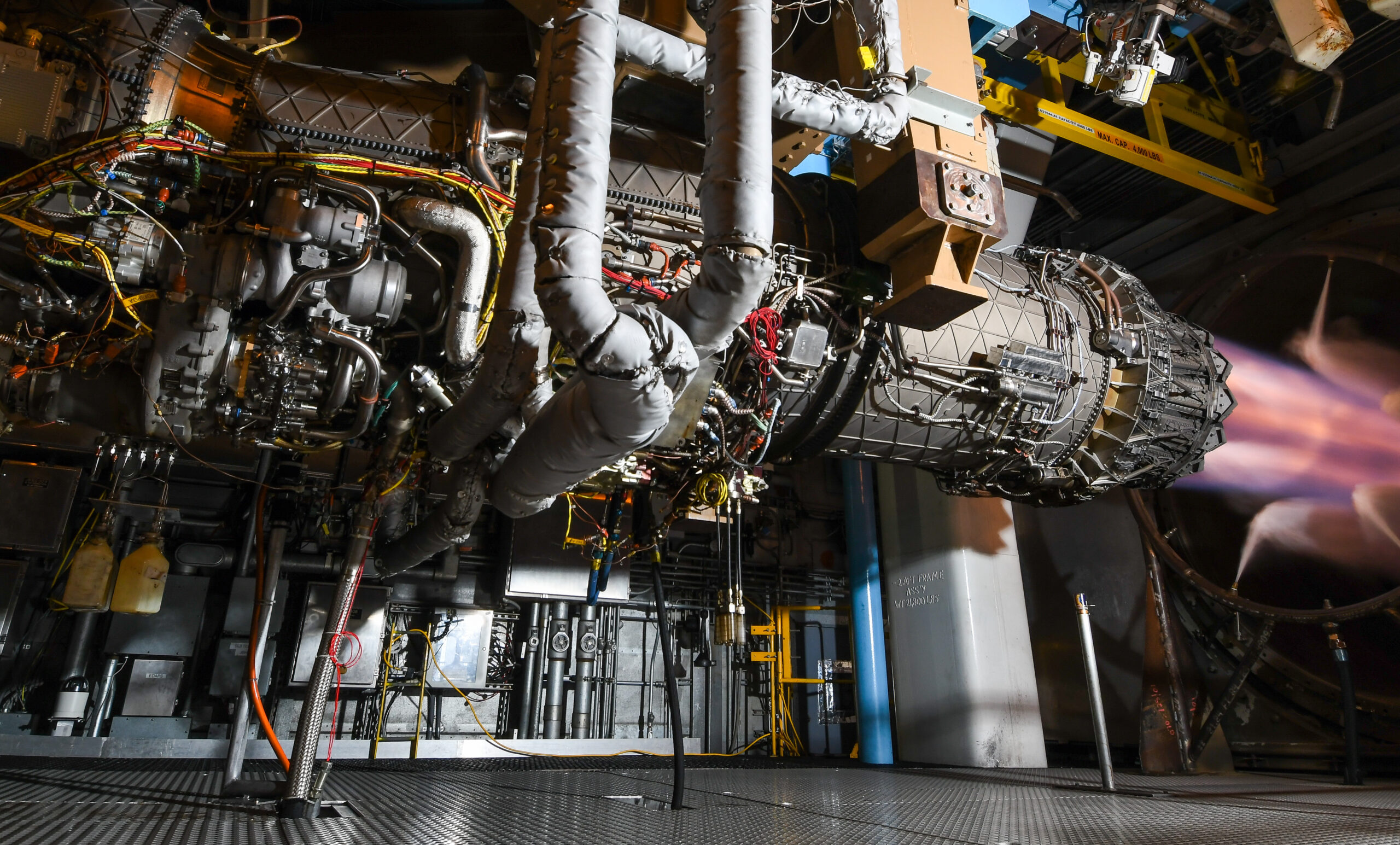

A Pratt & Whitney F135 engine undergoes accelerated mission testing in Sea Level Test Cell 3 at Arnold Air Force Base, Tenn., Nov. 15, 2021. The F135 is the engine used to power the F-35. (US Air Force/Jill Pickett)

WASHINGTON: Secretary Frank Kendall said today that the Air Force should waste no time in resolving a question that could result in a major expansion to the capability of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter: Is the service prepared to fund a new, adaptive engine for the jet, or will it choose more budget-friendly upgrade for the existing F135 engine?

“I think we need to make a decision about the future of the F-35 and get on with it,” Kendall told the audience at an event hosted by the Potomac Officer’s Club. And while Kendall added that he wasn’t sure what that ultimate decision will be, “I am hopeful that we will have one for the FY24 budget,” he said.

As the F-35 transitions to the more advanced Block 4 variant this decade, the jet will need either a new engine or an upgrade to its current Pratt & Whitney F135 propulsion system to have the power and cooling necessary to support new hardware and software upgrades.

The question is whether the US military should continue to fund one of the adaptive cycle engines as part of the Air Force’s Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP) — in which Pratt and Whitney’s engine faces competition from one made by General Electric — or opt for the lower cost option of enhancing the current F135. The latter option could still increase the F-35’s range and fuel efficiency, but to a much lesser extent than a brand new engine.

This summer, General Electric and Pratt & Whitney are slated to complete tests of two different adaptive cycle engines — GE’s XA100 and Pratt’s XA101.

RELATED: Can GE finally break through on the F-35 engine at a ‘critical decision point’?

Although the AETP program has been a “technological success,” it faces two major obstacles, Kendall said. “One is the high cost. It’s going to take several billion dollars in the five-year program to move through EMD [engineering, manufacturing and development] and get that program ready to be fielded and get it into production. The other is that, as it currently exists, those prototypes will not go to all three variants of the F-35.”

But the worst possible option for the Air Force would be to throw money to continue to develop those systems if the service will never be able to buy the end product, Kendall said. “I don’t want to loop along spending [research and development] money on a program that we either can’t afford or we’re just not going to get agreement on among all the different services,” he said.

Although the Air Force is just one of the Pentagon’s F-35 users — with the Marine Corps and Navy buying the F-35B short takeoff and vertical landing variant and F-35C carrier variant, respectively — it buys a majority of the planes and holds outsize power in terms of determining the future of F-35 propulsion.

The two AETP engines are configured to be a “drop-in” option for the F-35A conventional takeoff and landing model used by the Air Force. And while it’s the F-35 Joint Program Office’s job to compile future engine requirements from the Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps and chart a path forward, much of that decision will depend on whether the Air Force continues financing development of Pratt and GE’s adaptive engines and whether the service is willing to pay a premium for an engine variant that is different than other users, Lt. Gen. Eric Fick, then the Pentagon’s F-35 program executive, said in September.

During Farnborough Airshow last week, General Electric executives touted the performance upgrades that the XA100 could bring to the F-35, including a 30% increase in range, 20-40% improvement in kinetic performance, and the ability to double the energy output for on-board systems.

“From GE’s perspective, we really think that this is a critical decision point, and the decision is ‘What does the future of F-35 propulsion look like?’” said David Tweedie, vice president and general manager of advanced products for GE’s Edison Works division. “I think the one thing that probably all of industry and most of government will agree on is that something needs to be done. The debate is what path do you go on?”

Meanwhile, Pratt & Whitney has championed an upgraded version of the F135, which it has laid out to the F-35 program office in a series of “enhanced engine proposals.” Katherine Knapp Carney, the company’s chief engineer for the F135 program, told reporters in October that the most expansive suite of upgrades would increase the F135’s range and thrust by as much as 10%, while doubling the engine’s thermal management capability.

No matter which direction the Pentagon chooses to go, the decision will likely receive scrutiny from Congress. On July 22, Rep. John Larson, D-Conn., and 35 other lawmakers sent a letter to Bill LaPlante, the Pentagon’s acquisition executive, calling on the Pentagon to forgo further AETP development.

“Modernization of an existing fighter jet engine is a normal occurrence as capabilities and requirements change and does not warrant the risk and cost of a complete engine replacement,” the lawmakers wrote. “The F-35 program is already the most complex and expensive program ever undertaken by the Department. As the program begins to shift from development and production to long-term sustainment, we believe that now is not the time to initiate a complete engine replacement program.”

Air Force picks Anduril, General Atomics for next round of CCA work

The two vendors emerged successful from an original pool of five and are expected to carry their drone designs through a prototyping phase that will build and test aircraft.