An experimental Army robot, nicknamed Origin, during the Project Convergence 20 exercise at Yuma Proving Ground, Ariz.

WASHINGTON: The Army’s Artificial Intelligence Task Force is teaching AIs to share data and decide which intel is good enough to show a human, AITF experts told me. The tech will be tested in the service’s annual Project Convergence wargames this fall.

[Click here for more from the Army’s AI Task Force]

Douglas Matty

The objective isn’t to usurp a human’s role in decision-making, AITF director Doug Matty emphasized in an interview. To the contrary, it’s to empower them with highlights cherry-picked by computer out of masses of data – much of which isn’t accessible to a human user in any form today – without overwhelming them with trivial or unconfirmed reports. Experiments like Project Convergence, Matty argued, show that such an empowered human isn’t significantly slower than a purely computer-controlled approach.

“As we demonstrated with our ATR [Aided Threat Recognition] effort, having that person in the loop is not a huge time sink,” Matty told me. That finding stands in reassuring contrast to widely held worries that a human decisionmaker would slow the system down dramatically, giving an decisive advantage to unscrupulous adversaries willing to unleash killer robots without adequate human oversight.

“What we found was, is, by presenting the right information at the appropriate level of confidence, it actually accelerated the mission, because … you didn’t have to flood the individual user with a bunch of false detections” or low-probability potential contacts, Matty said. “We didn’t have to send all of the streaming video. We didn’t have to send all of the terabytes of information that the system was sensing. We only had to send those aspects that were truly critical to enable the man in the loop to take that next action.”

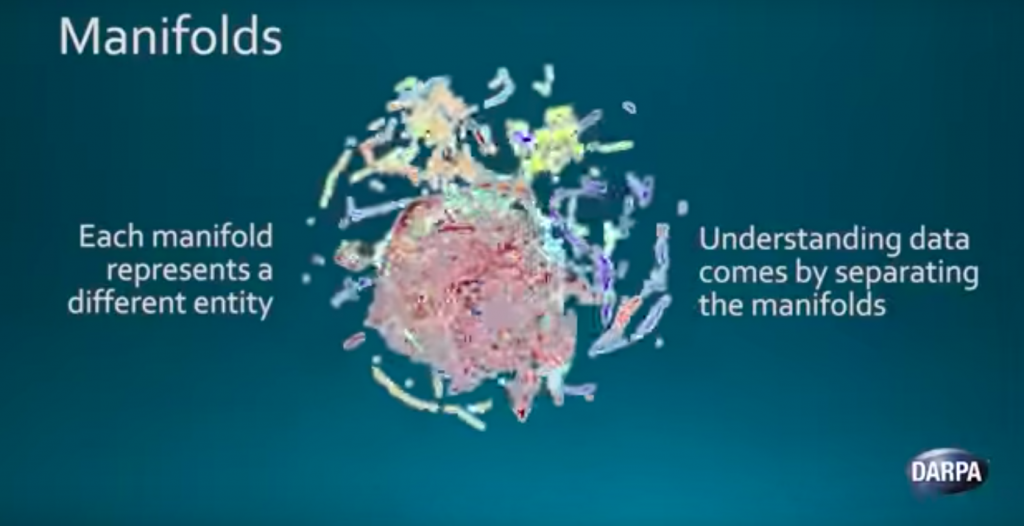

Modern machine learning AI relies on the fact that, in any large set of data, there will emerge clusters of data points that correspond to things in the real world.

Icebergs of Data

The US military – and its adversaries – know that mastering masses of data will be vital to future victory. The US in particular is trying to develop Joint All-Domain Command & Control (JADC2), a meta-network that pulls together data from across all the services in all domains – land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace – to figure out where potential targets are and the best way to take them out.

But all this data can’t just show up on some big screen in a command post somewhere, because human analysts couldn’t make sense of all those out-of-context numbers. So the AITF’s approach is for the machines to share data with each other and collaborate to figure out what’s worth presenting to the humans.

In Project Convergence 2020 last fall, Matty told me, the focus was on painting a picture of the battlespace that all the human operators could share – a Common Operating Picture or COP. For this year’s upcoming Project Convergence 2021, however, the AI Task Force realized the machines need to share all the data with each other before they share some of it with a human. “Before you present that information to the human, there’s actually another level … called the AI COP,” he said. “What that allows you to do is track… lots more potential entities, i.e., contacts.”

In essence, you have to teach good news judgment to machine-learning algorithms . The AI pulls data from multiple sources, collates and correlates it, tasks further sensors to corroborate, and then calculates how confident it is that any given contact represents a real target. If, for instance, you are getting a radar return, an infrared heat source, and a visual image of a tank from the same location, it’s much more likely to be a real tank than a blow-up decoy or radar-spoofing signal.

Then the AI has to decide which information is expected or routine and what’s surprising. That requires calculating what information theorists call bits of entropy. The more unexpected a piece of data is – say, a possible sighting of an enemy commando team over the hill from headquarters – the more it deserves calling to a human’s attention, even if the evidence is ambiguous.

“The good news,” Matty told me, “is there are well understood and successfully implemented approaches that allow us to deal with that uncertainty — and not only that, to understand what that uncertainty means to us in terms of operational implications.”

Now, this approach does involve machines tracking vastly more data than they ever show to a human being, Matty acknowledged, but that’s what happens already, anyway. A missile defense radar, for instance, may filter out low-and-slow contacts because it’s designed to look for ICBMs, not quadcopters. A 5th-generation aircraft like the F-35, festooned as it is with sensors, collects such a tremendous amount of data – visual, radar, radio, infrared – that not all of it may actually find a user.

Data is like an iceberg, Matty said: “There’s already multiple levels below the waterline …that humans can’t see.” Artificial intelligence can let humans see the hidden underbody of the iceberg before they hit it.