The USS Zumwalt (DDG-1000) is a high-tech, high-cost package of futuristic technologies.

WASHINGTON: Shipbuilding is under pressure in the 2017 budget, but that didn’t stop the Chief of Naval Operations from sketching out his service’s “next warship” this morning.

He wants ships built from the keel up for cyber and electronic warfare. He wants modular designs that can be updated at the speed of Moore’s Law. And he wants sailors with both the digital savvy to exploit all this technology and the old-fashioned independence to act on their own when the enemy takes the network down.

Adm. John Richardson

Richardson also wants this quickly — at least compared to the 20-year timelines of many major weapons programs. “I don’t think that the next generation that will man that ship is in grade school [today],” he said. “I think we’re going to have to do that much faster.”

The need for speed also underlies the decision to replace the UCLASS drone bomber program with the more modest Carrier-Based Aerial Refueling System, CBARS.

“My motivation was really to get something going,” Richardson told reporters after his public remarks at the American Enterprise Institute. “Let’s get something on deck … where we can start to learn about integrating unmanned aircraft into the air wing.”

“We don’t want to preclude future opportunities” for such things as an unmanned stealth bomber, Richardson said. “[We want] a path into the future that wouldn’t preclude all of the things that everybody wants — I want it as much as everybody.” But a less ambitious aircraft can get in the fleet faster at lower cost and risk.

The X-47B drone plugs into an aerial refueling tanker for the first time.

Getting to tomorrow faster requires reform today. “The rate at which technology’s being introduced, it’s [measured in] months,” Richardson said. “We can’t even get the paperwork together in that amount of time.”

Last year’s defense policy bill granted Richardson and the other service chiefs new authorities over acquisition. “The ’16 National Defense Authorization act…allows me to exercise ownership, much more so, over Navy acquisition, and I look forward to exercising that,” he said. In particular, the CNO is working with the Office of the Secretary of Defense and Congress to build a “speed lane” that bypasses much of the current bureaucracy, initially for select priority programs but gradually expanding to include more and more procurements.

Richardson also wants to better educate the naval officers who write requirements — the official wishlists that all too often push programs to pursue unrealistic and unaffordable capabilities. “I think we do a pretty good job with [training] our budgeting team,” Richardson said. “Similarly, the program managers go down to Defense Acquisition University, [but] we’re looking to formalize a little bit more how to educate our requirements officers. so they know what is really, truly needed.”

“Are we looking to what’s the next generation? What does that look like with all these technologies, particularly with the advent of information warfare becoming the mainstream of our business?” Richardson asked. “What does the next warship look like?”

“You talk about digital natives. So many people who are coming into the Navy and the workforce in general are very adept and very comfortable with these digital technologies,” Richardson said. “I think that’s going to be a key part of the next generation of warship. It will also be digitally native, information native.”

A Navy electronic warfare technician.

That’s not true of most current warships, like the Navy’s mainstay Arleigh Burke destroyers, designed in the 1980s — with the last expected to retire in the 2070s. Such ships have been and will be repeatedly upgraded, but they weren’t built to accommodate modern electronics. Some advanced systems like lasers, railguns, or even new radars simply require more electrical power than most current craft can generate.

“The way we are incorporating information warfare now is we’re taking the platforms that we have and we’re making them very capable by adding systems on,” Richardson said. “[For] the next generation….information technology and information warfare will be in the DNA of the ship.”

“That platform may last the life of a traditional ship, 25 to 30 years,” Richardson said, “[but] we have to make it very much more modular or adaptable to improving technologies,” with rapid plug-and-play upgrades rather than periodic and painful overhauls.

“There’ll be an increasing percentage of that ship that’ll be riding that Moore’s Law curve [of computer processing power doubling every 18 months],” he said. In terms of payloads, in terms of sensors, all of that will be improving much more quickly.”

How big a ship are we talking about? There Richardson gave a tentative but intriguing answer.

“This is just speculation,” he said, “but I think the lethality and effectiveness of some of our systems going forward” — from missiles to jammers to lasers and railguns –“will cause us to think hard about…the value of size in and of itself and the shape of future warships.”

“You can get more and more capability, just [from] miniaturization, into a smaller package,” Richardson said. “What that means from a warship standpoint I think all has to be on the table.”

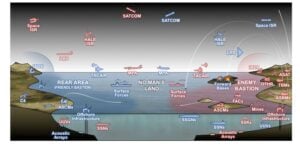

CSBA graphic of future naval warfare

Larger ships are historically harder to sink, but that may change, Richardson said. As smart weapons grow more numerous, more precise, and longer-ranged, he went on, “mass is becoming more and more a vulnerability than it is an advantage, so we’re going to be operating more distributed, dispersed.”

Such decentralized operations, however, may stretch the electronic apron strings that currently tie forward forces to higher headquarters. “Has that connectivity led to a dependence that may have gone past the point of being healthy?” Richardson asked. “Are they ready to act independently?”

Increasing connectivity has done great things for US forces — sharing intelligence, live drone video, detailed plans — but it has a dark side. You don’t want generals and admirals who micromanage their subordinates or deluge them with constant requests for data. You don’t want junior officers who wait for exhaustive intel and a mother-may-I from HQ before they act. And you don’t want anyone at any level going catatonic when enemy jamming and hacking makes the screens go blank — or fills them with misleading data.

“It’s tempting to think that all of that information is going to bring with it a lot more decision clarity,” Richardson said, “but I think when we really consider full-on information warfare, it’s going to be at least as challenging as right now, if not more so, to ferret through what’s real, what’s not, what’s relevant, what’s not, and make decisions.”

“We still need to continue address the fundamental nature of warfare, which is a competition between two thinking adversaries,” he said.

Sailors aboard the destroyer USS Sampson

“I’ve always been an advocate of decentralized operations because it allows those commanders that are out on point, distributed, to take best advantage of those opportunities and threats that only they will see…. a centralized commander will never have as full an awareness as the commander in situ,” Richardson said. “There’s opportunities that will come and go, that will be fleeting, and there just may not be time to check back.”

“Our asymmetric advantage is our creativity and ingenuity and our ability to act independently. We need to make sure that, though, we continue to foster that,” said Richardson said, noting that initiative is one of the core principles in his “Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority.”

“The very best idea might come from one of the most junior people in the room,” he said. “We need to be open to that [and] encourage them to contribute because they might have the one thing that saves the day.”

Shipbuilder Austal USA names Michelle Kruger as new president

Kruger had been serving as interim president since former chief Rusty Murdaugh resigned last spring.