Troops go over the top in World War I.

WASHINGTON: If you want a glimpse of future war, look back a hundred years to the bloody stalemate of the Somme, the cataclysmic battle of World War I. Instead of machineguns and artillery slaughtering soldiers in no man’s land, imagine smart weapons ravaging the air, land and sea. Instead of biplanes overhead, imagine swarming drones. Instead of the unreliable radios of 1916, with communications breakdowns throwing plans into chaos, imagine wireless networks hacked and jammed by enemies. The end result — the bodies — would look much the same.

Tom Mahnken

“Like the European powers at the start of World War I, we could find ourselves tremendously unprepared,” said Tom Mahnken, president of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. “We’re likely to find ourselves surprised, and unpleasantly surprised.”

That grim prospect is much on the minds of top Pentagon leaders, notably the Deputy Secretary, Bob Work, and the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. Mark Milley, who recently invoked World War I in a harrowing speech.

In 1914, “nations and empires marched off to their destruction, blind, blind to the changes in war,” said Milley. “Let us commit to not march into that abyss, blind to the changes. Let us commit for once, once in our history, to not be unprepared for that first battle.”

Now, Work and Milley aren’t resigned. They’re exploring new technologies and concepts — Multi-Domain Battle, the Third Offset Strategy, human-machine teaming — to give the US a winning edge. But it’s a truly brutal problem to solve, and a recent interview with the head of arguably the most influential thinktank on future conflict made clear that the hard thinking’s hardly begun.

Gen. Mark Milley

“It’s a good thing that the Defense Department senior leadership has begun talking about great power competition” — in essence, deterring Russia and China instead of bombing terrorist thugs — “but I think we are at the very early stages of thinking through what that’s going to mean,” Mahnken said.

The US has a generation of assumptions to unlearn. Since 1991, we’ve gathered intelligence, bombed targets and deployed forces around the world at will. Adversaries could bog us down in counter insurgencies, but they couldn’t interfere with us at long range.

That’s changing. Russia and China have resources the Taliban and Daesh can’t match, and they have had 26 years to invest them in ways to counter us.

“We have enjoyed a multi-decade period where the United States had a monopoly or near monopoly in precision strike — not just the weapons, but all the stuff needed to enable that,” Mahnken said. “In a security environment dominated by the spread of precision strike capabilities — and here, again, I mean not just the weapons but the sensors, the command and control — what does warfare look like and what are the options available to the United States?”

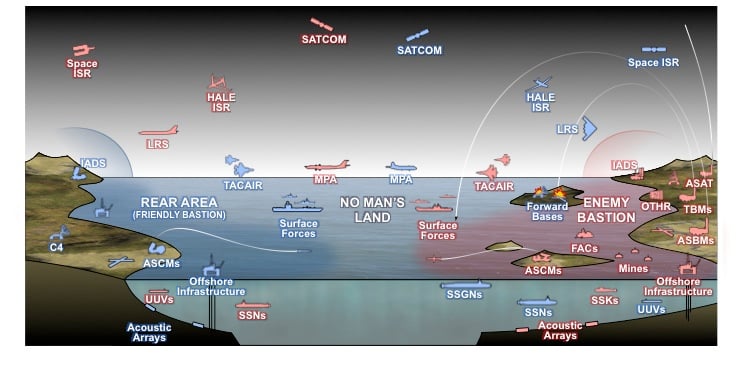

CSBA graphic

“Those capabilities are spreading,” Mahnken continued. “What we haven’t seen so far but we will — I’m depressingly confident in saying that — is a conflict between two sides both armed with these precision strike systems.”

That’s where the World War I analogy becomes painfully relevant. The great powers of 1914 had experience using machineguns, long-range artillery and aircraft. But they’d mainly used them in colonial wars against local rebels, tribesmen, and militia that did not possess anything like the capacity to respond in kind. With the exception of Russia and Japan, the lessons of whose 1904-1905 war went largely ignored, the great powers hadn’t experienced having these lethal technologies used on them.

In 1914, the outcome was trench warfare. Today, it’s Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD), a clunky term for layered defenses designed to keep US forces at bay. Instead of barbed wire and machineguns, imagine long-range missiles — anti-ship, anti-aircraft, and anti-ground target — backed by advanced aircraft, submarines, artillery, and invisible weapons such as hacking and jamming.

Robert Work

“So,” Deputy Secretary Work put it recently, “not only will our future army have to fight on a battlefield swept by precision munitions, but it’s going to be swept by persistent and very effective EW (Electronic Warfare) and cyber threats.” We can’t afford WiFi or radio chatter, Work warned. “If you emit, you die.”

“In the future battlefield, if you stay in one place longer than two or three hours, you will be dead,” said Gen. Milley the same day at the annual Association of the US Army conference. The increase in lethality, he said, will be like that between 1865 — the end of the US Civil War, which was already quite bloody enough — and 1918 — the end of World War I.

“Think of the difference between the smoothbore musket and the rifle, or between the rifle and the machinegun,” Milley said. “It is that kind of profound shift…. that is ongoing right now.”

Unlike the European powers pre-1914, the Pentagon today is already working to break the future stalemate. The Chief of Naval Operations, Adm. John Richardson, has even tried to ban the term Anti-Access/Area Denial because, he says, it suggests a no-go zone of death for US forces, when in fact we can break in.

“Adversaries think they can keep us out? I’m here to tell you they’re absolutely wrong,” said Work, lead author of the Pentagon’s Third Offset Strategy for high-tech, highly automated warfare. “We will quite frankly pound the snot out of them from range and in the close fight.”

New Offset Strategy technologies like missile defense lasers and long-range stealth bombers are like Britain’s 1916 answer to trench warfare, the tank. New tactics like Milley’s highly independent, constantly moving combat units are like Germany’s invention of 1916, the stormtrooper “infiltration tactics” used by all modern militaries. It’s also worth noting it took 23 years, and combining stormtroop tactics with much-improved tanks and aircraft that were all tied together with radio, to break the trench lines for good with blitzkrieg. Hopefully, will take fewer years and lives to crack Anti-Access/Area Denial.

New Offset Strategy technologies like missile defense lasers and long-range stealth bombers are like Britain’s 1916 answer to trench warfare, the tank. New tactics like Milley’s highly independent, constantly moving combat units are like Germany’s invention of 1916, the stormtrooper “infiltration tactics” used by all modern militaries. It’s also worth noting it took 23 years, and combining stormtroop tactics with much-improved tanks and aircraft that were all tied together with radio, to break the trench lines for good with blitzkrieg. Hopefully, will take fewer years and lives to crack Anti-Access/Area Denial.

“The intellectual history of Anti-Access/Area Denial goes back to the early to mid-1990s,” said Mahnken, when both US analysts and potential adversaries studied the weak points of the US war machine that had won the 1991 Gulf War. Most of the effort up till now has been persuading people that A2/AD was the driving threat.

“A lot of the analytical work in the recent past was about understanding Anti-Access/Area Denial,” said Mahnken. “Okay, that is or will be the new reality; now how do we operate in the face of A2/AD?

“The Third Offset Strategy is part of that,” he told me, but there are many others. One major, seemingly mundane concern for Mahnken: simply stockpiling enough smart bombs for a protracted conflict.

Victory Garden poster from World War II.

“Look at Libya in 2011: Two of our best-equipped European allies almost went Winchester (i.e. out of ammo) in their stocks of air-delivered precision munitions. Against Libya!” exclaimed Mahnken. “It’s very easy to imagine a larger-scale conflict where the belligerents would essentially run down their stocks very early in a conflict — as happened on the Western Front in late 1914.”

In 1914, both sides went to war convinced of a swift victory, only to bog down in four years of total war so draining that several major belligerents collapsed. (Russia in 1917, Germany in 1918, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire — this last never to rise again). In 2016, the US has grown grudgingly accustomed to years of counterinsurgency and bombing campaigns, but could we mobilize people and resources for a protracted major war?

“We really stopped thinking about defense mobilization after the end of the Cold War, more or less a quarter century ago,” said Mahnken. “What will mobilization look like in the 21st century? We won’t be planting Victory Gardens…. but we will have to mobilize our societal, our industrial resources in one way or another.”

“The US margin of superiority, the US margin of error, is diminishing,” Mahnken said. “In that situation, the need for strategic thinking goes up.”

Lockheed wins competition to build next-gen interceptor

The Missile Defense Agency recently accelerated plans to pick a winning vendor, a decision previously planned for next year.