WASHINGTON: With an eye on growing Russian and Chinese jamming capabilities, the SASC has ordered the Pentagon to provide Combatant Commander’s alternate position, navigation and timing (PNT) systems to GPS within two years.

WASHINGTON: With an eye on growing Russian and Chinese jamming capabilities, the SASC has ordered the Pentagon to provide Combatant Commander’s alternate position, navigation and timing (PNT) systems to GPS within two years.

“I think this shows that the committee is taking the jamming and spoofing threats to GPS seriously, and it is prompting DoD to focus its efforts on countering these threats,” Todd Harrison, space expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), said.

In Section 1601 of the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), SASC says the two-year deadline is “consistent with” urgent needs voiced by commanders in the field. DoD must:

- Prioritize and rank order the mission elements, platforms, and weapons systems most critical for the operational plans of the combatant commands;

- Mature, test, and produce for such prioritized mission elements sufficient equipment—

(A) to generate resilient and survivable alternative positioning, navigation, and timing signals; and

(B) to process resilient survivable data provided by signals of opportunity and on-board sensor systems; and - Integrate and deploy such equipment into the prioritized operational systems, platforms, and weapons systems.

“We see this as a really good thing, and a really positive development for DoD and the nation,” Dana Goward, president of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation, told Breaking D. Pointing to China’s effort to develop a robust PNT system, he added that: “We in America, both the Department of Defense and the civilian side, have become so complacent that we have let essential capabilities wither and stagnate.”

The SASC language, and the overall issue of GPS jamming, is likely to be a topic of discussion at Wednesday’s meeting of the National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) Advisory Board, experts tell us.

Commanders in the field have increasingly been slapping DoD with “joint urgent operational needs” for equipment that does not need to rely on GPS because their current systems are increasingly being jammed and/or spoofed, these sources said.

“But, they are getting no love from the Pentagon,” one insider said. This is in part because DoD officials don’t want to undercut the costly GPS III program, designed to include improved anti-jam features including the higher-fidelity M-Code signal for military users, the source said.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimates that the 10 GPS III satellites being built by prime contractor Lockheed Martin will cost $5.8 billion (a 31.8 percent increase from the original baseline; and the long-troubled Operational Control Segment (OCX), being built by Raytheon, at $6.2 billion (a 68.1 percent increase).

GPS III satellite, Lockheed Martin image

As Breaking D readers know, the GPS III program is finally moving forward after years of delay. The next GPS III satellite, Space Vehicle 3, is set to launch tomorrow on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. In a conference call with reporters on Friday about the upcoming launch, Col. Edward Byrne, chief of the Medium Earth Orbit Space Systems Division, said GPS III has three times the navigation accuracy of current GPS II satellites, and eight times more power — “and that helps with the anti-jamming capability of the spacecraft.”

Further, The Space Force announced in April that it had accepted as operational Lockheed Martin’s latest anti-jam upgrade to the software system for the stopgap operational control system, called Ground Operational Control System, built to fill in until the full OCX is available (currently planned for circa 2023).

However, a number of experts believe that those improvements to GPS III are not enough. In an April 13 op-ed in National Defense magazine, former Air Force chief scientist Gene McCall argued that DoD is “overselling” GPS III jam resistance to the detriment of both military and civilian users. McCall charged:

“Military coded GPS III signals will still be incredibly weak compared to the strength of the signals commonly used to disrupt them. Rather than an eight-fold improvement, GPS III would have to improve by a factor of 10 million to begin defeating the threat.

Second, “eight times more resistant to disruption” only applies to coded signals for military users with equipment that has not yet been built. The vast majority of GPS users and critical infrastructure will see no improvement at all.”

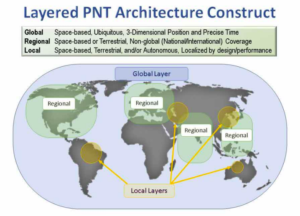

DoD itself in November 2018 quietly put out a PNT strategy document that acknowledges that GPS vulnerabilities are systemic to the nature of a satellite-based system, and calls for a “layered system” including terrestrial-based options and regional networks.

The SASC language doesn’t specify what specific non-GPS technologies they have in mind that could provide backup PNT capabilities — although an aide said the language is not in response to the committee’s concerns about the potential for the controversial Ligado 5G mobile communications network.

“They are looking for solutions that would provide alternative signal sources (which could be from other satellites, including non-U.S. GNSS systems) and for receivers that can process ‘data provided by signals of opportunity and on-board sensor systems.’ The later part could include using things like comms signals coming from other systems (think proliferated commercial LEO systems, for example) to triangulate one’s position,” Harrison said. (Non-US Global Navigation Satellite Systems include Europe’s Galileo, Russia’s GLONASS and China’s newly completed Beidou constellations.)

DoD and the services, most notably the Army, do have a number of efforts underway to provide GPS back-up. These include the Army’s developing WarLoc that would use inertial guidance units embedded in soldiers’ boots; and DARPA’s Spatial, Temporal, and Orientation Information in Contested Environments (STOIC) program looking at three technical areas: “1) earth-fixed navigation using very low frequency (VLF) signals; 2) deployable optical clocks based on technology developed under the DARPA QuASAR program; and 3) precision time transfer and ranging over data links.” But none the these efforts is very far along.

Several experts noted that SASC in its 2018 NDAA mandated that the Department of Transportation (DoT), in tandem with DoD and the Department of Homeland Defense, test technologies that could provide GPS backups.

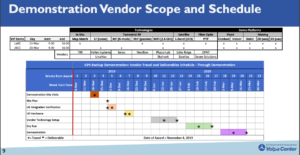

DoT issued its request for proposals (RFP) in May, seeking tech-demo ready capabilities “that are capable of providing backup positioning, navigation, and/or timing services to critical infrastructure (CI) in the event of a temporary disruption to GPS.” The RFP added that the demo “also is expected to encompass technologies capable of providing complementary PNT functions to GPS by either expanding PNT capabilities, including cross checks, or extending them to GPS or Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS)-denied or degraded user environments.”

“The interesting part to me is the last part of the section that instructs DoD to coordinate with civil agencies ‘to enable civilian and commercial adoption of technologies and capabilities for resilient and survivable alternative positioning, navigation, and timing capabilities to complement the global positioning system.’ The committee views this as a civilian problem as well, and they want DoD to share the technologies it develops with civilian users if possible,” Harrison said.

Sources say those demonstrations have wrapped up, and DoT is in the process of writing its report. According to DoT’s website, these could be carried on trucks or drones, or on constellations of small satellites in Low Earth Orbit.

For example, one potential solution tested is “eLORAN” — for enhanced Long Range Navigation — that uses radio towers to transmit signals. (The original LORAN systems were developed by the military just after WWII, but the technology has significantly improved since the Coast Guard finally dropped its LORAN program in 2010. Indeed, South Korea for example is now implementing eLORAN infrastructure for nationwide use, one source said.)

The technologies DoT has been testing are all supposed to be ready or nearly ready to field (“with a Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of six or higher,” according to DoT’s May 3, 2019 Request for Information.) However, experts say there is a big question as to whether or not any of them is any more ready than DoD’s efforts to be fielded within two years.

“That seems like a very unrealistic timeline,” said Brian Weeden, director of program planning at Secure World Foundation.

Army’s chief data officer outlines plan for new hierarchy of ‘data stewards’

The service’s new policy empowers “mission area data officers” for warfighting, intelligence, business operations, and enterprise IT, as well as institutionalizing what have been “ad hoc” data duties across the service, David Markowitz told Breaking Defense.