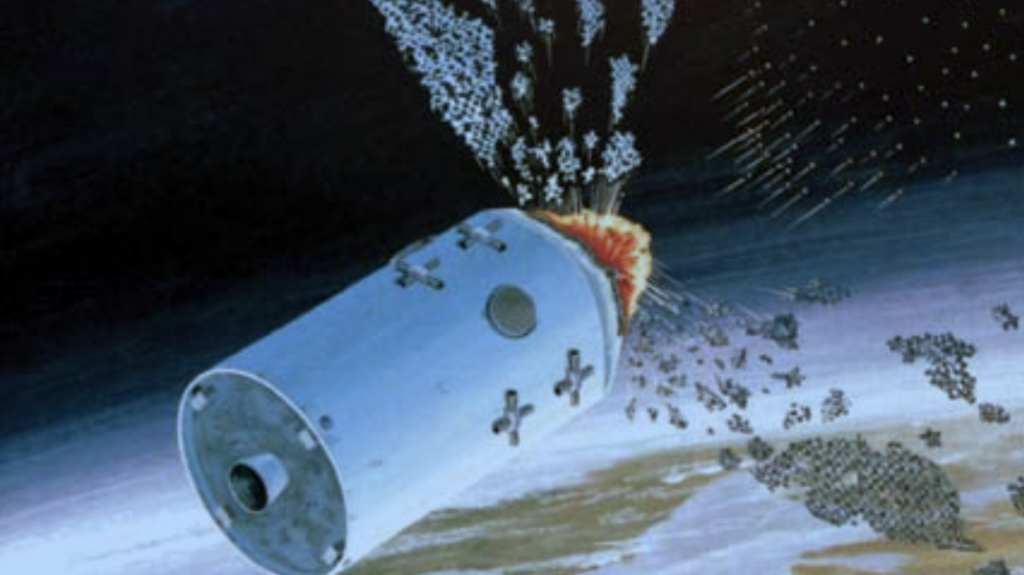

Artist’s rendering of a destructive ASAT strike. (Graphic: DoD)

WASHINGTON — When the United Nations working group attempting to hammer out international norms to govern military activities in space reconvenes on Sept. 12, on the table will be a formal resolution offered by the US for a ban on testing of destructive anti-satellite missiles, Breaking Defense has learned.

The US move is being announced later today at the second public meeting of the National Space Council, chaired by Vice President Kamala Harris, in an effort to convince other countries to follow in Washington’s footsteps. Harris in April announced the US pledge to refrain from the use of ground-based direct ascent ASATs that use kinetic energy to smash up satellites, prior to the first meeting of the UN Open Ended Working Group on Reducing Space Threats (OEWG).

The resolution was presaged in late August by Eric Desautels, acting deputy assistant secretary for arms control, verification and compliance at the State Department during a webinar sponsored by George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute and The Aerospace Corporation.

“It’s one thing to announce a unilateral commitment, but there’s a lot of work that is required to develop that shared understanding of the commitment, get broad international acceptance of it, and have it as a norm of responsible behavior,” he said. “And I think we’ve got a plan.”

One possible approach, he elaborated, would be introducing a “non-binding resolution” at the UN General Assembly’s First Committee, which handles peace and security issues. The General Assembly’s committees begin their annual meetings in September and the full assembly comes together in December.

“We could submit a resolution that would call on all countries to not conduct such direct ascent based missile tests,” Desautels elaborated. “The resolution would allow countries to go on record regarding their support, creating that shared agreement among the majority of UN member states, while increasing political pressure on countries that have plans for future ASAT tests.”

Desautels further pointed out that the UN General Assembly does not require consensus to pass, only a majority vote.

Up to now, only Canada and New Zealand have officially made the same unilateral pledge. However, sources involved in the UN initiative say that several other nations are expected to get on board during the course of next week’s meeting, which will focus directly on what specific actions by other states national governments perceive as threatening. (The ones to watch are the United Kingdom, Australia and Brazil.)

The European Union, while not going as far as formally adhering to the US concept — which is not a surprise, given that all 27 members would have to agree — welcomed the US effort in a statement [PDF] filed with the UN in advance of the OEWG meeting.

“The EU and its Member States consider these tests as irresponsible. Such activities are dangerous and highly destabilising; they may lead to deteriorating confidence between space actors, increase the perception of threats, and could trigger an escalation of violence and potentially could have catastrophic consequences,” the paper explained.

“In this context, the EU and its Member States welcome the commitment made by the United States, and joined by Canada and New Zealand, not to conduct destructive, direct-ascent anti-satellite missile testing,” the paper added.

Further, in Sept. 6 submission to the UN [PDF], Germany and the Philippines also characterized “Destructive testing or actual use of direct ascent anti-satellite missiles” as “irresponsible behavior.”

Daniel Porras, Secure World Foundation’s director of strategic partnerships and communications, praised the US initiative.

“The US is leading by example, calling on States to restrain themselves in a way the US already has,” he said. “This first step makes a lot of sense in terms of improving safety and security in space. Hopefully, the rest of the world will see it that way.”

Discussions Or Arguments

While sources involved in the UN meeting said that much of the discussion will be educational, with panels addressing different types of threats in space — ground-to-space, space-to-space and space-to-Earth — there are serious concerns that things could devolve into a finger-pointing exercise between the US and its rivals Russia and China.

The challenge for the OEWG chair, Hellmut Lagos Koller of Chile, will be to prevent such squabbling, Porras said. The key, he added, will be to keep the meeting — and especially those nations with less skin in the space game — focused on the fact that irresponsible and threatening behavior in space actually affects all nations.

Diplomats are keeping a particularly keen eye on Moscow for potential monkey wrench throwing as the talks resume, given that Russia opposed the creation of the OEWG and have been seeking to constrain its work via procedural arguments.

Indeed, in a Sept. 8 “working paper” [PDF], the Russian delegation to the Conference on Disarmament asserts that the OEWG discussions must be strictly limited to “military threats” that are leading to the brink of hostilities, rather than problems arising from the “peaceful uses” of space.

Thus, the paper argues, discussions of many issues considered critical by the US and many Western nations — such as debris, close approach and proximity operations around the satellites of other countries, and orbital congestion — should be relegated to the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space in Vienna rather than the OEWG.

“[T]he Russian Federation considers intention to place weapons in outer space as the main external military danger, and disruption of the functioning of outer space monitoring systems as the military threat,” the paper stresses.

Textron, Leonardo bank on M-346 global experience in looming race for Navy trainer

“The strength we think we bring is that [the Navy is] going to go from contract to actually starting to turn out students much quicker than any other competitors,” a Textron executive told Breaking Defense.