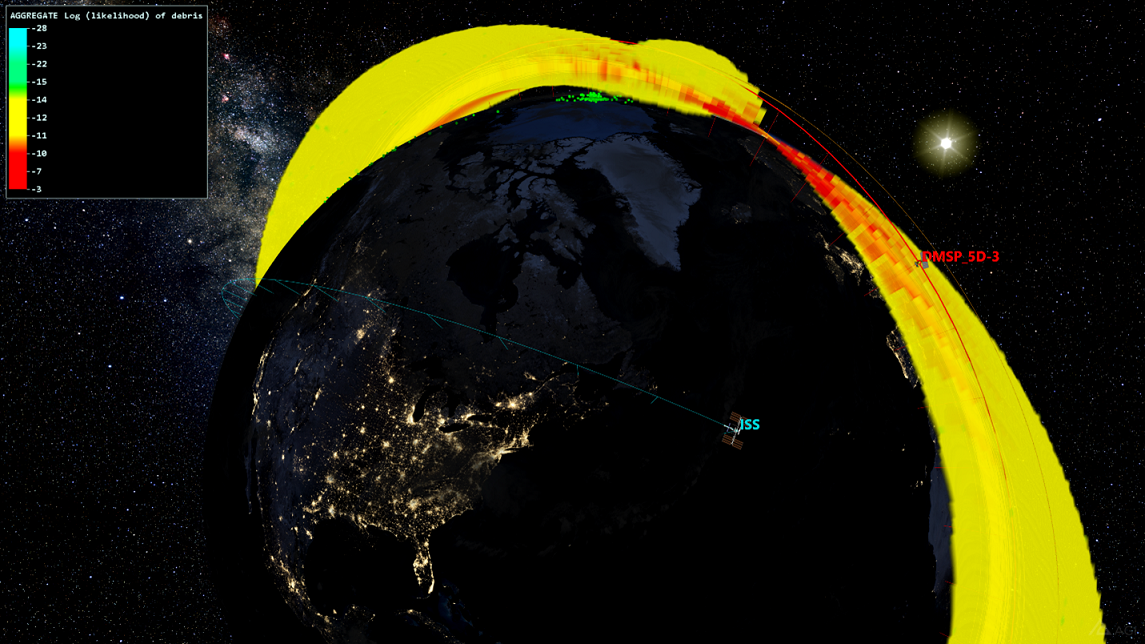

Path of the debris from Russia’s Nov. 15 ASAT missile test over the first 24 hours after impact with the Soviet-era Cosmos 1408 satellite, according to COMSPOC. (COMSPOC/CSSI volumetric analysis, with rendering by AGI, an Ansys Company)

WASHINGTON — A senior Space Force commander said today that “in no way” can the US “forgive” Russia for what he called its “reckless” anti-satellite (ASAT) test that blasted hundreds of pieces of debris into orbit last fall.

Lt. Gen. Stephen Whiting, commander of Space Operations Command, said he was willing to give China a little leeway for its destructive 2007 ASAT test, as the country was a “relatively nascent space power” at the time.

“But you absolutely, in no way, can forgive the Russians for doing that less than a year ago as this historic and sophisticated space power,” Whiting said during a CSIS event. “They knew what they were doing, and they were sending us a message.”

For its test, conducted on Nov. 15, 2021, Russia blasted one of its own satellites with a ground-launched missile, sending an estimated 1,500 pieces of debris rocketing out, imperiling numerous American satellites and forcing astronauts aboard the International Space Station to take shelter. An analysis by the space tracking firm COMSPOC showed the bulk of the debris should de-orbit by 2025.

In 2008, the US shot down a broken intelligence satellite in a strike that the administration of then-President George W. Bush insisted was not an ASAT test — though it still drew condemnation from China. This year the US is leading an international push to ban destructive ASAT missiles.

As for the exact message Russia was trying to send, Whiting didn’t elaborate, but made the comments during a general discussion about operating in “contested” space. The US military, and Space Force in particular, is racing towards a strategy of “resilience” in space — including relying on larger constellations of smaller systems as opposed to the traditional model of small numbers of exquisite satellites — under the assumption that at least some of its satellites could be taken out by an adversary.

RELATED: Space Force at 2: ‘Still a toddler,’ with all that brings

Beyond kinetic strikes, Whiting suggested he’s concerned about the vulnerability of Space Force’s assets to cyber attacks — mostly because he said that right now, he doesn’t know what the service needs to most guard against.

Whiting drew a contrast between a military base’s physical security, which is driven by security assessments of the threats the base might be facing, with cybersecurity for Space Force’s assets, for which there are certainly defenses, but relatively little information about the specific threats. Whiting said his service is investing in cybersecurity “at the weapons systems level,” assembling mission defense teams, monitoring systems, and building “higher level security” for overall network activity, as well as teaming with partners “outside the fence.”

“But we don’t yet have the same tools or intuitive understanding to say, based on the threat we’re seeing, have we done enough?” he said. “How much is enough in a resource-constrained environment? Where would I put my next dollar in this environment to help bolster that security? I don’t want to act like we don’t have any of those tools, but it’s not the same comprehensive understanding we have for physical security.”

Elsewhere in the discussion, Whiting touched on another topic of much conversation in the space industry: the likelihood of adversaries targeting not just US government-owned, but privately owned space assets that are doing work for the government or at least in the government’s interests. While it didn’t come up in the talk, the topic has been in the news lately related to Ukraine’s dependence on Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite constellation for communications in its fight against the Russian invasion — not to mention other private firms that have been egged on by the US government to help.

RELATED: To protect and maybe defend: NRO, SPACECOM ponder commercial satellite defense options

Were it to come to that, how would the US respond?

“I think it’s important to note there are combatant commands who have the mission of protecting and defending on orbit,” he said. “Let me just say broadly, just as in other domains, that if a commercial asset that the United States government had contracted with to provide a capability was held at risk, that becomes of interest to the United States government. And I think we will see that same dynamic play out in space, and there are processes for how we go about working with companies and then working with our own capabilities to defend” against such an attack.

China creates new Information Support Force, scraps Strategic Support Force in ‘major’ shakeup

A PLA spokesman said the Information Support Force “is a brand-new strategic arm of the PLA and a key underpinning of coordinated development and application of the network information system,” which would seem to indicate a sharp focus on networks.