WASHINGTON: Senate appropriators want to give the Army $75.4 million to kick-start its new scout aircraft, but key authorizers told us they are skeptical. (House appropriators are so far silent). The crucial questions: Can a manned, low-altitude, lightweight aircraft survive against the Russian threat? And can the Army afford the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA) along with its other Big Six priorities?

An industry day held Thursday provided details that reassured our industry sources. “The Army, I’ve got to give them credit,” said retired Maj. Gen. Rudy Ostovich, a former Army aviator who’d been uneasy about the early, vague reports. “I didn’t know all of the details. They kept it very close to their chest, (but having seen them,) if I were writing these requirements, I would do the same thing.”

Requirements are a hard part of any program, but they’ve been particularly all over the place in the Army’s repeated attempts to replace its aging OH-58 Kiowa scout helicopter, now retired from service. The cancelled RAH-66 Comanche was a high-tech, radar-evading stealth chopper, but it’s the sound of rotor blades that normally give a helicopter away, not radar, which they can often fly under. The cancelled ARH-70 Arapaho was much less ambitious, a militarized Bell 407. The stillborn Armed Aerial Scout never saw a prototype. In the meantime, the Army turned to a combination of AH-64 Apache gunships — a much heavier helicopter — and drones to do reconnaissance, with unsatisfactory results.

Now, for FARA, the Army wants a new kind of scout that has to be three things at once:

- a fast aircraft that can fly at 180-205 knots, far faster than a conventional helicopter, which drives the service towards the compound helicopters and tiltrotors prototyped for the Future Vertical Lift competition;

- a small scout that can hide more easily than the Apache or even fly down city streets, which favors Sikorsky’s relatively compact S-97 Raider over Bell’s much broader tiltrotor designs;

- a highly automated aircraft that can fly with two human pilots aboard, one, or none, depending on the mission (aka optionally manned) and that operates in concert with a robotic wolfpack of up to half a dozen drones, both including mini-drones launched by the aircraft itself like missiles.

Working closely with drones, ground troops, and precision artillery to pull apart Russian-style air defenses, the Future Armed Reconnaissance Aircraft is meant to scout deep into hostile territory, finding targets for US strikes and hitting targets of opportunity itself.

Ostovich is confident Army pilots will be up to the challenge, if their new fast, agile aircraft get both a full suite of countermeasures against anti-aircraft missiles and proper support from other Army units and the Air Force. “Operations forward of the FLOT (Forward Line of Own Troops, i.e. the front line on the ground) will be highly coordinated joint operations just like what we did in 1990-91 in Desert Storm,” he told me. “Dick Cody’s Apache battalion that blew a hole in the Iraqi integrated air defense system at the beginning of the kinetic phase of that operation didn’t do it by themselves. They were part of a much larger joint force. Beyond that, our Army combat aircraft are equipped with a full suite of ASE (Aircraft Survivability Equipment) and our crews are well trained in their use.”

Hill sources are less certain. True, Army helicopters ranged far and wide with relative impunity in Afghanistan and Iraq, where anti-aircraft missiles were rare and small arms were the main threat. But in the 2003 invasion, an Apache battalion that attempted a deep raid over Karbala without artillery support got badly shot up by lightly armed Iraqis.

Against a high-tech adversary like Russia, scout aircraft might not be able to advance at all without US tanks, missiles and infantry close at hand to help destroy enemy radars and anti-aircraft batteries. That would force fliers to stick close to friendly ground troops, making long range and high speed largely irrelevant.

In this highly lethal vision of the future battlefield, only expendable unmanned aircraft would try penetrating dense air defenses. Human pilots would not be obsolete, but investing heavily in manned, high-performance aircraft would probably give place to higher priorities.

Too Many Priorities?

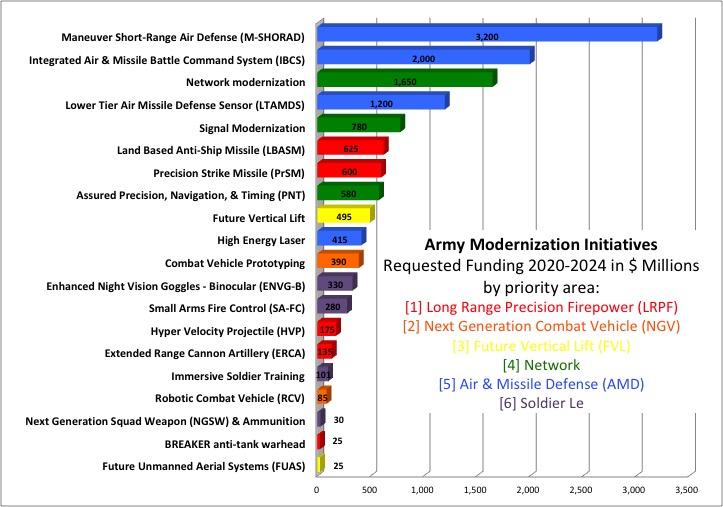

The Army has a lot of priorities to fund. Driven by Russian and Chinese threats, its Big Six plan calls for long-range precision-guided artillery, new armored ground vehicles, new aircraft, a hacking- and jamming-resistant network, new air and missile defenses, and new soldier equipment — in that order. Even within the No. 3 priority, known as Future Vertical Lift, the Army wants not only a new armed scout to replace Kiowas but also a new assault/transport aircraft, called FVL Capability Set 3, to replace its thousands of UH-60 Black Hawks, a much bigger expense.

Just to confuse matters more, Future Vertical Lift is both the name of the Army’s No. 3 priority and the name of the Joint project to build a family of advanced aircraft to replace all four services’ current helicopters. Bell and Sikorsky (partnered with Boeing) have invested hundreds of millions of their own money into Joint Multi-Role (JMR) demonstration aircraft geared at the midsize FVL Capability Set 3.

Now the Army is focusing on the lighter scout aircraft, which corresponds mostly but not entirely with what the joint FVL effort defines as Capability Set 1. FVL CS1 envisions a hybrid scout/utility aircraft capable of carrying up to six passengers, like the Sikorsky S-97, but the Army prefers a smaller, purebred scout with only two crew seats.

The joint version of Future Vertical Lift is also moving at a slower pace than the Army wants. Joint FVL is moving to a full-scale formal program of record that will start fielding the midsize Capability Set 3 in the 2030s. That’s fine for the Marines, who in recent years replaced or rebuilt their vertical-lift fleet with V-22s, AH-1Zs, and UH-1Ys, but less fine for the Army, which still has lots of older CH-47s and UH-60s.

So the Army was already interested in getting Capability Set 3 earlier, and now, our sources tell us, the service wants to get the armed scout even faster than that. The Army probably can’t afford to buy both light and midsized aircraft at once, the logic goes, but it could slip in a relatively small number of relatively small scouts before the larger program for larger aircraft ramps up to its full, expensive height. It’s still not clear whether this accelerated effort would be a pure Army program or at least partly under the joint umbrella of FVL.

Can industry deliver on time? Sikorsky (now part of Lockheed) seems most confident, since their S-97 Raider is in the light scout class and already flying, although the test program was on hiatus for 10 months after an accident. Even if the Army really doesn’t want the S-97’s six crew seats, it shouldn’t be too hard build a slimmed-down model.

We’re back! Yesterday, our S-97 Raider completed a successful flight. We’re eager to demonstrate the high speeds and extraordinary maneuverability of this second generation X2 Technology. #avgeek https://t.co/QXFx85PdtT pic.twitter.com/rWC5DtXv17

— Sikorsky (@Sikorsky) June 20, 2018

By contrast, Bell is heavily invested in tiltrotors, which are larger. The V-280 is smaller than the V-22 and the company is developing the even smaller V-247 drone. However, the fact that tiltrotors always have two large, widely separated propeller/rotors means they take up more space than helicopters with comparable payload, either conventional helicopters or compound helicopters like the S-97 Raider. That said, Bell has extensive experience and could come up with something; it would be playing catch-up but is definitely in the game.

Other competitors include two European firms already flying prototypes — Airbus’s X3 compound helicopter and Leonardo’s AW609 tiltrotor — and two American firms, Karem and AVX, that have done relevant design work. The Army has said it may award up to six design contracts, enough for all the firms listed in this article, but only two will get contracts to build prototypes by 2023. The safe bets are those two prototypes will come from Sikorsky and Bell, but then again, Army’s increasingly ambitious modernization program keeps on surprising us.

France, Germany ink deal on way ahead for ‘completely new’ future European tank

Defense ministers from both countries hailed progress on industrial workshare for a project that they say “will be a real technological breakthrough in ground combat systems.”