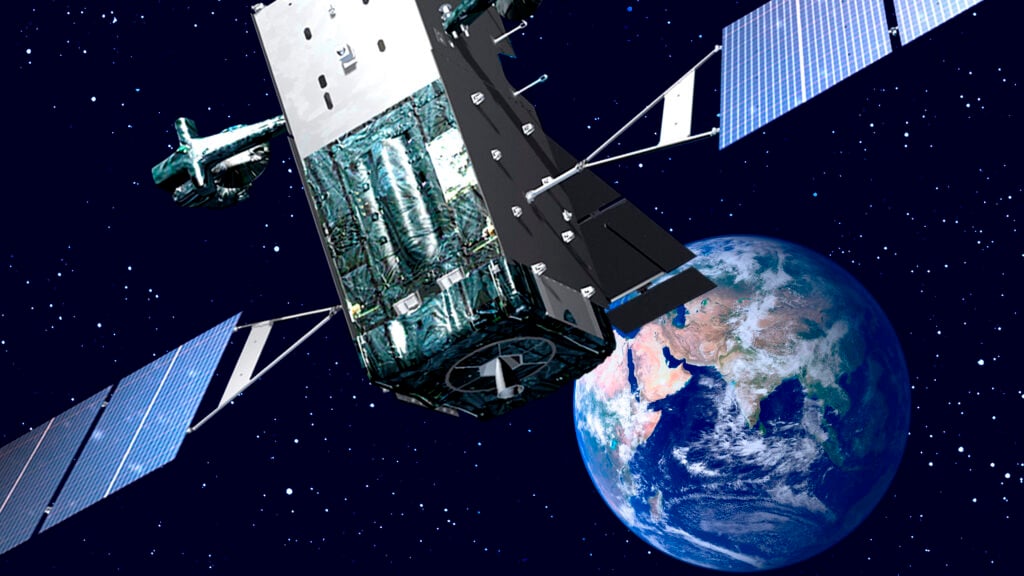

Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS) satellite. (USAF image)

WASHINGTON: The Space Force plans to launch the final satellite in its Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS) missile warning constellation on Aug. 4, putting a bow on the long running but often troubled program.

“This launch represents the conclusion of the production and launch phase, and the commencement of the satellites’ critical missile detection and early warning mission,” Maj. Matt Blystone, program manager at the Space Force’s Space Systems Command (SSC), told reporters today at a pre-launch briefing.

SBIRS, conceived in 1996, was designed to replace the elderly Defense Support Program (DSP) satellites, the first of which was launched in 1970. The operational constellation comprises three satellites in Geosynchronous Orbit (GEO) and two hosted payloads on classified satellites in Highly Elliptical Orbits over the poles. Lockheed Martin is the SBIRS prime contractor and Northrop Grumman the payload integrator.

Assuming the Thursday launch goes as planned, the last of the satellites, SBIRS GEO-6, is expected to be up and running by “late spring, early summer” next year, Blystone said. The time between now and then will be filled with various tests of the satellite and its subsystems.

RELATED: NRO, Air Force may co-fund future space-based ISR tech, Kendall says

Technically, SBIRS GEO-6 and its predecessor SBIRS GEO-5 launched last year were produced to replace two of the older SBIRS satellites (the birds have an expected 12-year lifetime) in the constellation. While there have been modifications to the satellite bus and its propulsion, the IR sensors on board both GEO-5 and GEO-6 are exactly the same as those on the first four of their sister satellites, said Col. Dan Walter, senior materiel leader at SSC’s Strategic Missile Warning Acquisition Delta.

But in reality, he explained, the service will continue to operate the older satellites basically until they die — including the older SBIRS and even the DSP satellites the newer generation was supposed to replace.

“We use the satellites as long as we possibly can,” he said during the briefing.

Walter explained that the more satellites are available, the better operators can detect and follow an adversary ballistic missile in flight by provided what is known as “stereo” coverage from the multiple sensors.

“With stereo coverage, the more looks that you have at any missile launch, the more accurate the reporting on that particular asset is,” he said. “So, GEOs -1, -2, -3 and -4. And the DSPs that are on orbit are going to continue to operate as long as possible.”

SBIRS once was the poster child for how not to do space acquisition, vastly exceeding its originally planned cost estimates and falling significantly far behind schedule. Starting in 2001, the program racked up not one, not two, not three, but four so-called Nunn-McCurdy breaches that required restructuring and downgrading planned requirements.

The Nunn-McCurdy law requires a notification to Congress if a Defense Department program has cost growth greater than 15%; if the overrun tops 25% then the Pentagon has to certify that a) the program is critical to national security and b) no viable alternatives are available.

In a 2021 report [PDF] on DoD’s missile warning and tracking programs, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) summed up SBIRS roiled history:

“Total program costs for SBIRS grew approximately 260 percent from $5.6 billion in 1996—when the Air Force initiated the program—to $20.3 billion in 2020, and launch of the first satellite was delayed roughly 9 years, from 2002 to 2011. Even after restructuring the program several times, SBIRS continued to face development challenges, including test failures and technical issues that resulted in cost growth and schedule delays on the third and fourth satellites. Additionally, the fifth and sixth SBIRS GEO satellites experienced technical issues leading to delays.”

But in recent years, the program has mostly put its woes behind it, according to the congressional watchdog.

“Still, the program has largely overcome cost, schedule, and other technical issues on recent GEO satellites,” the GAO report stated.

Indeed, Blystone noted that the SBIRS GEO-6 bird was “completed almost a month ahead of schedule.”

Further, the new Lockheed Martin bus, called LM 2100, used for SBIRS GEO-5 and -6 also will be used for the Space Force’s Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared System (Next-Gen OPIR) satellites being developed to replace SBIRS. The first Next-Gen OPIR satellite is slated to launch in 2025, with the full constellation of five — three in GEO built by Lockheed Martin and two in polar orbits built by Northrop Grumman — expected to be on orbit by 2029.

HASC chair backs Air Force plan on space Guard units (Exclusive)

House Armed Services Chairman Mike Rogers tells Breaking Defense that Guard advocates should not “waste their time” lobbying against the move.