An Air Force F-35 Lightning II Demonstration Team aircraft takes off from Tinker Air Force Base, Oklahoma, May 25, 2021. (U.S. Air Force photo by Paul Shirk)

WINDSOR LOCKS, Conn. — For several years, a problem has been brewing for Lockheed Martin’s F-35: future upgrades will make the jet run even hotter than it does now, more than its current cooling system is believed to be able to handle.

In the near term, Pentagon officials expect that a high-profile upgrade to the plane’s F135 engine will avoid most of these cooling issues. But in the longer term, the military fears future aircraft upgrades needed to keep pace with threats decades down the line will push the heat factor even higher, and officials have recently suggested they’re casting about for new cooling options.

Their choices boil down to this: either upgrade the plane’s current Power and Thermal Management System (PTMS) made by Honeywell Aerospace, or seek solutions for a new PTMS from competitors like Collins Aerospace, which has bet some serious time and money on the possibility.

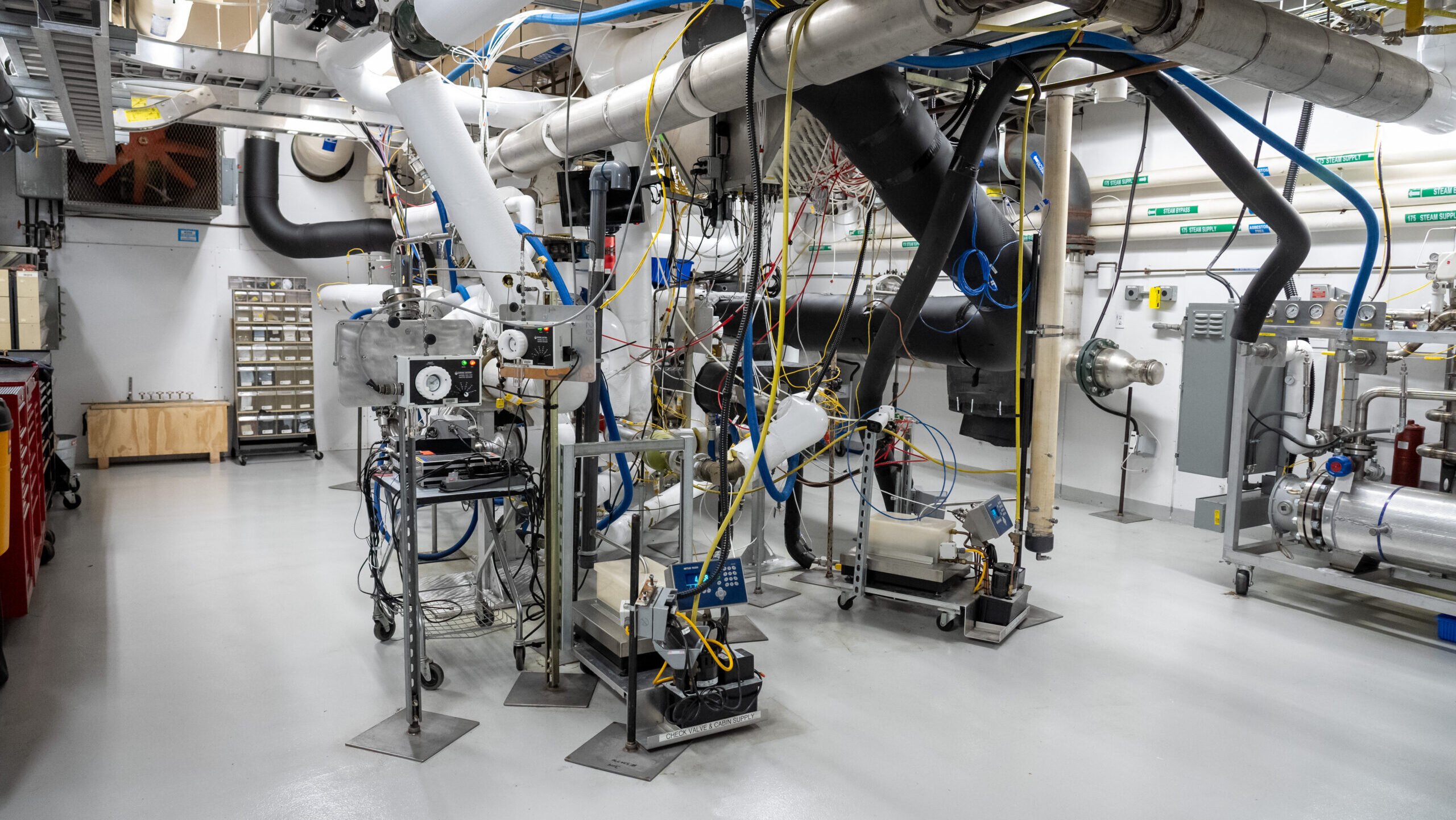

Earlier this week reporters from a small number of outlets, including Breaking Defense, were invited to a lab at Collins’s facilities here, where years of internal investment has culminated in a new cooling apparatus for the F-35 called the Enhanced Power and Cooling System (EPACS), what would be Collins’s PTMS replacement.

Rigged up to simulate certain operating conditions of the stealth fighter and instrumented extensively to measure results, the EPACS has demonstrated a key benchmark, Collins announced Tuesday: a capacity for 80 kilowatts of cooling.

“We’ve been investing over the last five years, trying to get this technology … to a point where, number one, we felt that it was ready for the warfighter. And then number two, we had mitigated, burned down the majority of the risks required to have this ready for primetime for the EMD [engineering and manufacturing development] phase of any type of program that were to come,” Ira Grimmett, Collins vice president of environmental and airframe control systems, said in a briefing with reporters at the facility where the EPACS is housed.

As a potential competition looms, Honeywell President for Defense and Space Matt Milas argued in a statement to Breaking Defense that upgrading the existing PTMS architecture is the “proven, low-risk” option, and emphasized a competition to replace it would bear significant costs and risks for the F-35 — from concerns over concurrent testing to complications with the current maintenance infrastructure. No other defense firms have publicly thrown their hat in the ring for a potential cooling system showdown.

A Years-Long Cooling Conundrum, With Worse Looming

The cooling problem stretches back to at least 2008 when, according to previous reports from the Government Accountability Office, Lockheed discovered that the stealth fighter’s PTMS needed to pull more of what’s known as bleed air off the fighter’s engine than originally expected to help cool off its subsystems, taxing the engine beyond its design specifications. Beyond cooling — a critical feature for stealth aircraft that have to mask their thermal signatures — the PTMS also serves other vital roles like providing emergency electrical power.

The decision to siphon more bleed air from the engine has proved a costly tradeoff, which risks greater maintenance for the powerplant that GAO estimates will cost as much as $38 billion throughout the program’s lifecycle.

The Joint Program Office (JPO) said the next significant set of F-35 updates, collectively known as Block 4, is designed to work with the plane’s current F135 engine made by Pratt & Whitney, but agreed the “cooling demands” posed by the Block 4 upgrades “will increase Operation and Sustainment (O&S) costs over the lifetime of the program.”

The coming engine upgrade also offered by Pratt, known as the Engine Core Upgrade (ECU), “with its increased performance, will be able to meet the demands that the Block 4 capabilities place on the engine and eliminates the O&S impact. A modernized PTMS solution, paired with the F135 ECU, will enable beyond Block 4 capabilities,” program office spokesperson Russ Goemaere said in a statement to Breaking Defense.

RELATED: F-35’s Block 4 upgrade 55 percent over target costs, up $1.4 billion since last review: GAO

To get to that “modernized” PTMS, however, the JPO has not yet formally announced whether the incumbent Honeywell PTMS will be upgraded or replaced wholesale through a competition.

Still, there are indications the Pentagon is leaning in that direction. When discussing the F-35’s modernization challenges in a December congressional hearing, Program Executive Officer Air Force Lt. Gen. Mike Schmidt, for example, indicated he was open to broader industry involvement.

“There are a number of great suppliers of power and thermal management systems out there that I want to be in this discussion and will be in this discussion. But I’ve got to do some really good engineering work first to try to bring all of that together,” the general told lawmakers.

When asked whether the Pentagon has decided to hold a competition for the PTMS, Goemaere told Breaking Defense that “the JPO is completing its market research. Once the research is complete it will decide on how best to bring greater cooling and power to the warfighter.”

The F-35 program has queried industry for input, most recently releasing a request for information (RFI) that set a minimum goal of 62 kilowatts of cooling and a target objective for 80 kilowatts — the metric Collins said it hit this week. In layman’s terms, that means that if the F-35’s subsystems generate 80 kilowatts of heat, a PTMS solution has the capacity to sufficiently cool them off.

Inside The EPACS Lab

Outside of a thick brick wall that houses the EPACS prototype, chief engineer Matt Pess and his team fired up the system for a test run. As the test proceeded, a virtual graph actively measured four key elements: simulated heat that on the jet would be generated by its avionics, the temperature of air that is pumped into the cockpit and the temperature of liquid coolant both before and after it’s pushed to heat sources.

As the mock avionics in the lab generated greater heat, the graph showed temperature readings start to spike. But the EPACS responded, settling temperatures at target ranges. According to Pess, that’s about 40 degrees Fahrenheit for the cockpit air and 59 degrees Fahrenheit for the coolant liquid that’s supplied to the jet’s avionics.

Speaking over the vacuum-like roar of the EPACS, Pess said that the system is designed to operate at the 80 kilowatt capacity indefinitely through all elements of the F-35’s flight envelope. During the simulated demonstration, the EPACS actually slightly beat that 80 kilowatt goal, offering about 83 kilowatts of capacity.

The EPACS is designed to use less bleed air than the current PTMS does, Pess said, and be compatible with all three variants of the F-35. Though new cooling technology concepts are out there, he emphasized the EPACS is based on traditional air-cycle technologies common in commercial and military aircraft.

“There’s nothing really special,” he said. “It’s just the application of what we’ve done on previous [programs].”

The JPO’s RFI says the government expects a solution to be ready to field in roughly the 2032 timeframe. The EPACS, Pess said, could be ready to be cut into production “as early as 2030.”

Collins Aerospace’s EPACS instrumented in a lab in Windsor Locks, Conn. (Collins Aerospace photo)

Integration ‘Challenges’

For incumbent supplier Honeywell, company officials have warned that attempting to integrate a new PTMS could spell trouble for the F-35 program overall. In interviews with Breaking Defense last year and statements this week, Honeywell executives described the costs: billions of more dollars, as well as unacceptable developmental risk.

And as reported by Aviation Week, Honeywell asserts that getting up to higher cooling capacity ranges will require invasive changes on the aircraft. For example, it could mean enlarging the tubes that carry the liquid coolant as well as widening holes drilled into the aircraft that the tubes pass through.

“The PTMS is not a ‘plug and play’ system, it is the heart and circulatory system of the F-35, and is highly integrated in the F-35 air vehicle design from inception designed to perform in 14 different operational modes,” Honeywell’s Milas told Breaking Defense this week, emphasizing as well that the system meets current requirements.

By upgrading the existing PTMS architecture, Milas argued the military would avoid “technical and schedule risk for concurrent redevelopment and aircraft testing of critical functionality.” Additionally, he claimed doing so would retain the current supplier base and enable easier retrofits.

Asked about the potential for a new PTMS to require other significant changes to the aircraft, Collins’s Pess demurred, saying that, “I think we can only speak to specifically what the system is capable of providing, and the rest of that integration would have to be a question for Lockheed.” Lockheed, he said, is “still trying to understand” what other changes would need to be made on the aircraft, which “would be something that’s within their purview, not ours.”

The EPACS prototype is being simulated with the “boundary conditions around the PTMS,” Pess said, whose “conditions” are informed by previous studies with Lockheed.

“I think the real question as we get into integration is, what else on the airplane needs to change, and does that have any impact on those boundary conditions?” Pess said when asked how integration might challenge the performance shown in the lab.

In previous interviews, Honeywell has additionally accused RTX of impropriety, suggesting unfair coordination between its subsidiaries Collins and Pratt. Pratt officials denied the charge at the time, and Pess said that though Pratt was involved in previous studies, a “firewall” was placed between it and Collins when Honeywell’s concerns came to light. The essential interface information for the PTMS, according to Pess, comes from plane-maker Lockheed, not Pratt.

Though Collins says EPACS has demonstrated key features in a lab, many considerations stand in the way of putting it on the jet. One factor among many is its weight: Pess said Collins is not aware how much the current PTMS weighs, though the company has offered that information and more on EPACS for the JPO to evaluate. “I’d be very surprised if you could find a way to reduce weight while having this much capability,” he said.

“We’re gonna get into challenges with integration. We’re gonna have to make changes to the system. When we’re going through that effort with the Lockheed team and understanding exactly where those hard points are on the platform, we’ll be able to absorb that and still provide the same capability,” Pess said.

“We have a lot of work to do with Lockheed if they were to launch an EMD [engineering and manufacturing development] program. There’s no doubt about that,” he added. “We want to make sure that as little of that becomes a problem as possible.”

Air Force awards SNC $13B contract for new ‘Doomsday’ plane

The win is a major victory for the firm in a competition that saw the surprise elimination of aerospace giant Boeing.