TECHNET 2019: America’s four-star combatant commanders need a global network to coordinate different services, agencies, and allies against threats — especially in cyberspace — that metastasize beyond a single theater. Making full use of that technology will also require new planning processes, new training, and — hardest of all — cultural change.

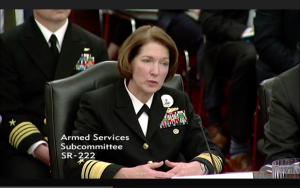

“The most important thing for all of the COCOMs is interoperability — joint and coalition/allied interoperability,” Vice Adm. Nancy Norton said, “because we have to be able to fight across all of the COCOMs….. seamlessly, regardless of where we’re fighting.”

The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Joseph Dunford, has long pushed for improved trans-regional planning and coordination to counter global threats. The formal boundaries between theaters of war don’t matter much when malware can cross the globe in minutes.

“The ability to [contain] fights in a region is pretty much gone,” Norton told the AFCEA TechNet Cyber conference in Baltimore this afternoon.

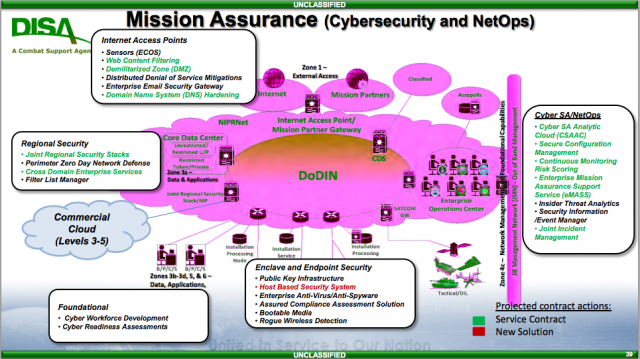

Norton plays a unique dual role as both the lead defender of the military’s internal Department of Defense Information Network (DODIN) and the director of the Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA), which builds and operates much of that network. In both capacities, she supports all four armed services and all 10 inter-service combatant commands. While DISA was traditionally a back-office support organization, its role in running networks day-today has increasingly put it on the digital front line.

“We cannot get lulled into creating services and capabilities for peacetime only,” Norton said. “We have to prepare for a multi-domain battle” — that is, conflict intermingling operations on land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace — “with an increased emphasis on cyber warfare.”

“A fight in cyperspace will not remain tidily in one COCOM area of operations,” added Rear Adm, Kathleen Creighton, Norton’s deputy at what’s called Joint Force Headquarters-DODIN, which was created precisely because no one theater command could defend the network worldwide. To ensure global communications continue even in the face of high-tech attacks, Creighton and other officials told reporters, DISA is contracting for a wide range of options, from different types of satellites to multiple, redundant undersea cables.

JFHQ-DODIN issues a daily “cyber tasking order” on the latest threats and security measures that goes to every COCOM, every defense agency and field activity, to the Department of Homeland Security, and even to selected foreign allies. Right now, the order and the information it contains are only shared abroad with America’s closest allies, the Five Eyes (UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, with the fifth being the US), said Col. Paul Craft, JFHQ’s director of operations. “We’re working to expand that [and] share that more broadly,” Craft said, “[but] it obviously has to be done one by one,” taking the time to vet each potential foreign partner.

Networking The Force

Building a network that goes around the world, connecting the four-star strategic leaders, is just the start. Ultimately, data needs to flow up and down the ranks, all the way to what’s called the tactical edge: the individual aircraft, vessels, vehicles, and even foot troops for whom timely intelligence is a matter, not of 1s and 0s, but life and death.

Of course, US adversaries want to make sure those 1s and 0s don’t make it to the troops who need them. Russian and Chinese forces are well versed in hacking networks, jamming and physically destroying communications nodes with long-range missiles and artillery.

“Our adversary’s going to constantly be contesting us in this space, trying to disconnect us, degrade us, spoof us,” said Dana Deasy, the Pentagon’s hard-charging Chief Information Officer. “Do we know how we’re going to fight through?”

Deasy is the Pentagon’s leading crusader for cloud computing, which boils down to connecting far-flung offices, bases, and units to centralized servers — though some of those servers may be small enough to fit in a soldier’s backpack. Even so, he’s quick to acknowledge that an enemy may cut off your access to the cloud. Frontline forces in particular need the ability to keep local copies of the specific data they need — a concept called “store it forward” — so they can keep fighting even if they lose communications, Deasy said.

But the biggest challenge isn’t bandwidth: It’s bureaucracy. Coping with the new and more amorphous kinds of conflict will require changes to process, training, and ultimately culture.

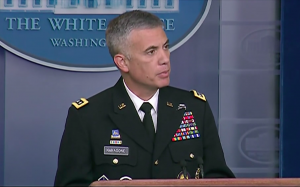

“We have absolutely no problems working at the four-star level,” said Gen. Paul Nakasone, the chief of Cyber Command, one of the 10 COCOMs. “I would tell you, when I talk to my counterparts, they clearly get it — but between myself and the action officer level, there’s about three different layers.” Many of those military middle managers haven’t got the broader perspective the four-stars are forced to have by working with the other services, civilian agencies, and foreign allies every day. Officers brought up in traditional planning processes and information systems may struggle with new, amorphous kinds of threats, especially in cyberspace.

For example, Nakasone said, in the traditional Military Decision Making Process taught to budding staff officers, “we identify Named Areas of Interest and Targeted Areas of Interest.” Historically, that meant focusing intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance on specific geographical areas — but today, he said, the target could be something intangible, like “data.”

“We didn’t think about that when I was going through the military schools,” Nakasone said, “and now we need to.

“Show me the curriculum that a young cadet takes that starts to teach them how to think about data, the importance of data, and data as an offensive, and defensive [tool],” agreed Deasy. “There’s a lot more that we could be doing there, that I don’t think we’re doing enough of, frankly…..We need to start introducing new skill sets into people when they’re very young coming in.”

Into The Grey Zone

“Change is upon us,” Nakasone said. “How do we apply non-kinetic power in a way that we haven’t done before? We’re very, very familiar with …. the planning process that goes to kinetic operations. Non-kinetic operations, I will tell you, are sometimes as important and need to be done, and we are working our way through that.”

Non-kinetic operations is military jargon meaning, in essence, anything you do besides blowing stuff up. It’s something the US struggles with in the generation of counterinsurgency, counterterrorism, and cyber conflict that have followed 9/11, but Russia and China have gotten scarily good at it.

“Our adversaries continue to operate below the level of armed conflict,” Nakasone warned the conference. “[They] continue to attempt to steal our intellectual property, leverage our personal identifying information, or attempt to interfere in our democratic process.”

Russia and China use this kind of grey zone operation — from hacking networks to fortifying artificial islands to seizing Crimea — to strengthen their position and undermine the US, without moving so blatantly they provoke the US to respond with its still-superior firepower. Without escalating to physical acts of war — never a great plan with nuclear powers — how does the US respond?

Cyber Command is fighting in the digital world every day, Nakasone said, in what he likes to call “persistent engagement” –a concept now embraced by key members of Congress. In layman’s terms, that means defending Defense Department networks, monitoring malicious activity, informing other agencies like domestic law enforcement, and selectively hacking back. (This last part blurs into cyber offense, especially since if you want the option to retaliate against someone if they ever attack you, you probably need to infiltrate their system, find vulnerabilities, and even ready malware before they hit you). “It’s a very, very effective model,” Nakasone said, “[which] we perfected during the recent mid-term elections.”

But the elections were just one battle in a much wider global war, and persistent engagement in cyberspace addresses just digital defense, not the full complexity of the grey zone. The fundamental problem? Modern conflict, especially but not only in cyberspace, blurs the lines the modern US military was built around — between four-star commands, between the different services and their domains, between the strategic and the tactical, even the fundamental distinction between war and peace. Adapting to this ambiguity will require not just new technology, but new mindsets.

Taking aim: Army leaders ponder mix of precision munitions vs conventional

Three four-star US Army generals this week weighed in with their opinions about finding the right balance between conventional and high-tech munitions – but the answers aren’t easy.